Blog Archives

Readers Library wartime paperbacks

The Readers’ Library had been a long-running series of cheap hardback books selling at 6d, often at non-traditional outlets such as Woolworths, and notable for their colourful dustwrappers with wrap-around illustrations. The business together with the associated printing company Greycaine, had been owned by Frank Grey and Ralph Hall Caine, son of the novelist Hall Caine. It was also associated with the Queensway Press, publishers of the Chevron / New Chevron paperback series in the late 1930s.

The main Readers’ Library series ran from about 1924 until the late 1930s when the business ran into financial trouble and went into receivership. After that it’s unclear exactly what happened, although bits of the business were sold off and the printing company certainly continued to operate. Like many publishing businesses at the time, much of it eventually seems to have ended up in the arms of Walter Hutchinson and his Hutchinson Group.

In the run-up to World War II, the Hutchinson Group, a sprawling conglomerate of publishing companies, had applied a scattergun approach to the problem of competing with Penguin in the paperback market. Over a period of just four years, it launched at least seven new series in ‘Penguin format’ – first the Hutchinson Pocket Library, followed in quick succession by the Crime Book Society, the Toucan Novels, the Jackdaw Library, the Hutchinson Popular Pocket Library, the Wild West Pocket Library and John Long Four Square Books.

As if that wasn’t enough, in 1940 three new series appeared from the Leisure Library, another branch of Hutchinson – the Wild West Library, the Crime Novel Library and the Romantic Novel Library. Whether this was a deliberate strategy to try lots of different experiments in the hope that one of them worked, or whether it was simply the result of a lack of coordination with the Group, I have no idea.

As wartime conditions and particularly the effect of paper rationing started to bite, there may have been a realisation that this was becoming unsustainable. Each of the series gradually petered out, serial numbering of the books came to an end and the uniform price of 6d was impossible to maintain. By about 1942 a price rise to 9d was inevitable (quickly followed by 1s and then 1s 3d), and the books were becoming very thin and cramped in accordance with the War Economy Standard.

You might have thought that the last thing this group needed was to bring in another publisher of 6d paperbacks or hardbacks. But that seems to be what happened. The Readers Library Publishing Co. joined Hutchinson, and at least two Chevron paperbacks appeared during the war with advertising for the Hutchinson Book Club, so presumably as part of Hutchinson.

Between about 1943 and 1948 there seem to have been almost no new titles added to any of Hutchinson’s pre-war 6d series. The separate brandings of Toucan, Jackdaw, Crime Book Society and so on were dropped until about 1948 when they came back in a rather different format. Instead the group appears to have temporarily dropped the idea of Penguin-style series branding and gone back to illustrated covers. Many of the early books from this period are shown as published by Hutchinson, others by Skeffington, Jarrolds or other companies within the group.

But then rather surprisingly, a lot of the paperbacks started to appear as published by the Readers Library Publishing Company in association with Hutchinson, or in association with one of the other group companies. I have examples of books published in association with Jarrolds, Stanley Paul, Hutchinson, Hurst & Blackett and The Grout Publishing Co., and there are no doubt others. Many have illustrated covers, but others have non-illustrated designs. There is no obvious series design, or uniformity, although in some ways the books are quite standardised. All have an advert for Hutchinson’s Universal Book Club on the back cover and adverts on the inside covers for ‘Super Shave’ shaving cream and ‘The little chap’ stain remover. They’re in conformity with the War Economy standards for book production, so with very cramped text, thin margins, thin paper covers and generally poor quality paper. In almost every respect except cover design, they look like a series.

The fact that all these are shown as published by the Readers Library Publishing Co. does seem to be an attempt to impose some consistency on the various paperbacks coming out of the Hutchinson Group. It’s strange then that in terms of the front covers, it seems to be such a free-for all. In some respects it represents a complete breakaway from the Penguin style, almost a reversion to what existed pre-Penguin, and maybe not before time. But it’s surprising how little uniformity of style there is, and still some of the covers are non-illustrated, in various formats.

None of the books are dated, but I have one, priced at 1s 3d and with a gift message handwritten in it dated 1944, so I guess this is from 1943 or 1944. Others priced at 1s 6d may be a bit later, but they all look like wartime production, or possibly immediately post-war, so overall they maybe cover the period from about 1943 to 1947. Most of the books are printed by the Anchor Press, but a few are printed by Greycaine, the former Readers Library printing company, by then owned by Taylor Garnett Evans and Co.

It seems to have been a temporary solution, a wartime attempt to shore up an arrangement that had become impossibly unwieldy. After the war the group would go off in different directions. But because thin wartime paperbacks are so fragile and ephemeral, and probably printed in relatively low numbers in the first place, this chapter in paperback history risks being lost.

John Long Four-Square Thrillers

Yet another new paperback series launched in the busy three or four years after Penguin’s launch in July 1935. Yet another in the Penguin format that I’ve repeatedly referred to – same size, same price (sixpence), typographical cover design with no cover art, dustwrapper in the same design as the cover, and so on. Yet another series from a part of the Hutchinson Group.

It completely baffles me why Hutchinson felt the need to launch another Penguin-style series in addition to the half dozen they already had, and perhaps particularly why they needed another series for thrillers from authors such as Edgar Wallace. The first four books in the John Long Four-Square Thrillers series, launched in September 1938, were all by Edgar Wallace (who had died in 1932). To highlight the point, the back cover of all the books featured an advert for Hutchinson’s Crime Book Society, with a list of titles in the series, including three by Edgar Wallace. Why could the new books not have appeared in that series?

Anyway they did launch another series and had to find a name for it, as usual employing little originality. Previous series from Hutchinson had followed Penguin in using a bird name – Jarrold’s Jackdaw Books and the Toucan Novels. After Penguin’s three coloured bands, Collins had introduced the White Circle and now John Long opted for four squares. Presumably they were attracted by the sense of solidity that four-square evokes, as well as by the prosaic description of the cover design. Except that the design does not really have four squares on it. You don’t need to be a mathematician to recognise that these are four rectangles, but certainly not squares.

Starting with four books by Edgar Wallace was a fairly clear statement of intent about the type of books that was to be expected from this series. The next batch of titles, in January 1939, was more varied in terms of authors, but much the same in terms of style, including titles from Sydney Horler and John Creasey. The 24 volumes in the numbered series from September 1938 to March 1940 included six by Edgar Wallace, five by John Creasey and four by Brian Flynn.

By 1940 of course wartime conditions were starting to bite, publishing programmes were reducing, paper was becoming more scarce and prices were rising. The volumes issued in March 1940 were priced at 7d rather than 6d and later (unnumbered) volumes increased further in price.

The lack of numbering after March 1940, in common with other Hutchinson series in this period, makes it difficult to be sure about exactly how many books were published. The checklist by Richard Williams lists 22 volumes at a shilling, published between September 1940 and around June 1941, but there are question marks against some of them and the books themselves now are very difficult to find. A quick internet search shows not a single copy of any of them currently offered for sale.

Possibly another six appeared around 1942 at 1s 3d, and then the series went into hibernation for the rest of the war, although two books described as John Long Four Square Thrillers appeared in 1945 in the Hutchinson Series of Services Editions, in the normal branding of that series.

Around 1948 to 1949 other books in John Long Four-Square branding appeared at 1s 6d in what was by then effectively a combined series of Hutchinson paperbacks. Again it’s difficult to say exactly how many, but possibly around 15 different titles, again mostly by John Creasey and Edgar Wallace, but also with several horse racing stories by Nat Gould described as John Long Four-Square Racing Thrillers.

Westerns for the troops

The 1920s and 1930s are often thought of as the Golden Age of crime fiction. When Britain went into the Second World War at the end of the 1930s, crime novels were enormously popular and much in demand amongst the services. Not surprisingly the Services Editions, produced for the armed forces, contain a high proportion of crime novels, mostly by British writers, although with a dash of American influence.

But the 1920s and 1930s had also seen growing popularity for westerns, a much less home-grown product – although arguably the country house settings of many British murder mysteries of the period were just as alien to the average British soldier as the Arizona desert.

Collectors of Penguin Books will know that wartime crime novels are the most difficult to find – it’s presumed because they were so avidly read that they fell to pieces. But in the Services Editions there is little doubt that Westerns are the most difficult to find – and again we can only presume that that’s because of their popularity.

Collins was the most prolific publisher of paperback westerns before the war and so was in the best position to offer them in Services Editions, and there’s a review of the thirty-five or so Collins Westerns on this post.

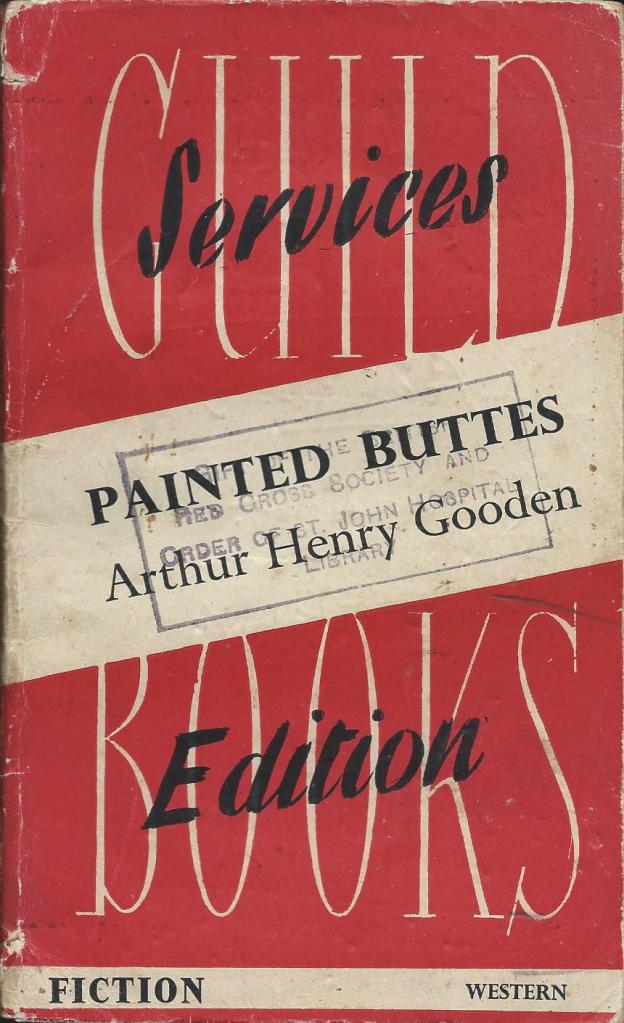

But they were far from the only publisher responding to the evident demand for westerns from the troops. The other main series of Services Editions, from Guild Books, included around ten to a dozen westerns, possibly more, as given their rarity, westerns may well account for several of the missing books in the series, for which no copy has been recorded.

In the Guild Books series, westerns shared a category with crime, mysteries and thrillers, all in red covers, but were identified as westerns in the bottom right corner, if it wasn’t already clear from the title. Many of the separate publishers who contributed books to the series didn’t publish westerns, but George Harrap, Cassell & Co. and Robert Hale were among those who did. There was also at least one western from Collins, although it’s slightly odd that they should have contributed books to the Guild series alongside their own series of Services Editions.

I don’t think that any of the individual titles are much remembered today, if indeed many westerns are. Authors such as George B. Rodney and James B. Hendryx are barely household names in their own households, and several of the author names, such as the unlikely sounding Bliss Lomax and Amos Moore, are pseudonyms anyway.

There is though one western story in another series of Services Editions that does claim a sort of lasting fame. The Hodder & Stoughton Services Yellow Jackets series has at least four westerns in it, including ‘Bar 20’ by Clarence E. Mulford. By 1944 when it appeared, this was already a classic of the genre – first published in 1906, and the first of a series of novels by Mulford to feature Hopalong Cassidy.

So far as I know, there are no westerns in other series of Services Editions, but there is at least one amongst the Hutchinson ‘Free Victory Gift’ books. Copies of ‘Feud at Silver Bend’ by J.E. Grinstead were given a celebratory new wrapper and included in the million books given by Hutchinsons to be distributed to troops.

Hutchinson’s Wild West Pocket Library

This feels almost like a postscript to my previous post on Hutchinson’s Crime Book Society, and maybe in the end that’s what the series was to Hutchinson. But it must have started off with much more optimism.

Hutchinson launched the Crime Book Society in June 1936 and the Wild West Pocket Library followed in October of the same year. Four books were published simultaneously to launch the series, but I can only assume that they sold badly, as no more books were added for almost two years after that. Whether it was the choice of titles or authors, or some failure of marketing, I can’t tell, but they were clearly not a success.

Perhaps it was just that Collins had launched its Wild West Club series only two months earlier and there was not enough of a market to support two apparently very similar series. Perhaps Collins had the better authors, or the better stories. Even their series was relatively slow to get going in comparison to the crime series, although it did in the end last a long time.

Whatever the reason, there was no follow up from Hutchinson to the first four titles until July 1938, when two more were published and even then the format was rather different, so that they hardly look like the same series.

The first four books had an image of a group of cowboys on horseback stretched diagonally across the front cover and came in at least two different colours, green and red. The dustwrappers were largely identical to the covers, except that the price of 6d is shown only on the dustwrappers. By the time the later two books were published in 1938, green had been generally accepted in the market as the colour for crime and yellow as the colour for westerns, so both books are in yellow and have a revised cover design with a smaller line of cowboys in silhouette and the title in a white circle. It looks to me like a bit of a mess of a design and certainly not as striking as the design of the earlier books.

The books were presumably no more successful than the first four had been as they were the last books to be added to the series. Only six books ever appeared.

By 1940 though they must have been willing to try again, as through the Leisure Library, a different part of the Hutchinson group, they launched another very similar attempt, this time branded the ‘Wild West Library’. This series did at least make it as far as twelve titles, although in the end it too was relatively short lived.

Hutchinson’s Crime Book Society

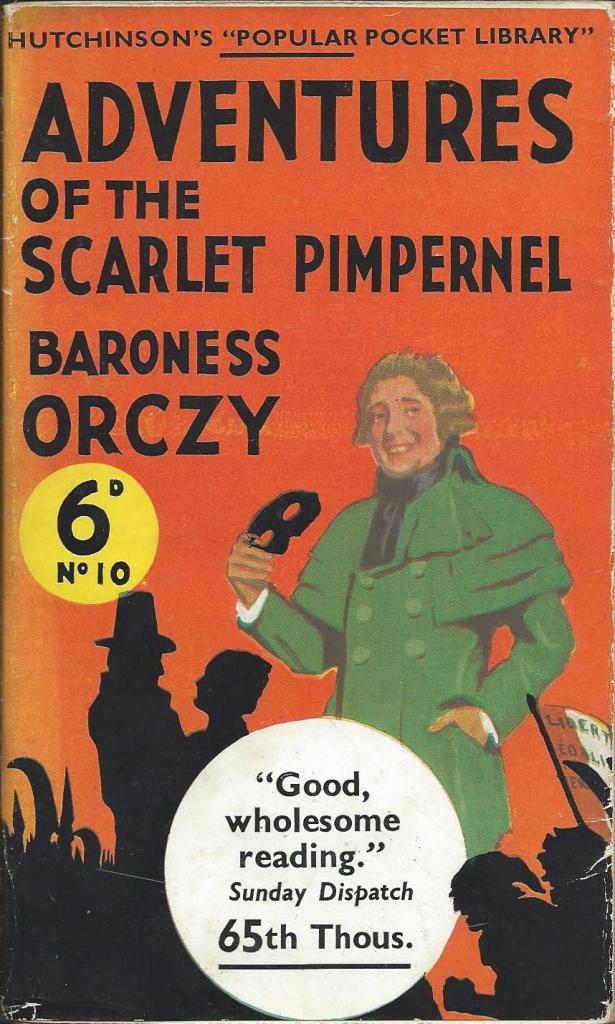

When Penguin launched in July 1935, Hutchinson as one of the existing publishers of 6d paperbacks, had to respond quickly. Hutchinson’s Pocket Library, in a very Penguin-like format, started just three months later in October 1935. It was followed by a rash of other series in a similar format from different parts of the Hutchinson Group over the next few years, including Jackdaw Books, Toucan Novels and Hutchinson’s Popular Pocket Library.

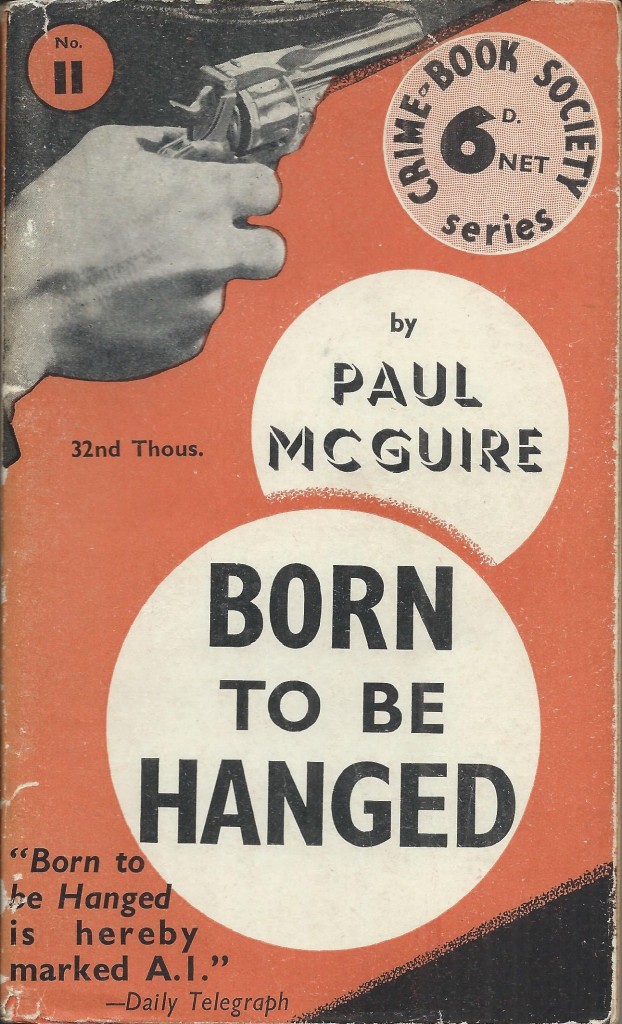

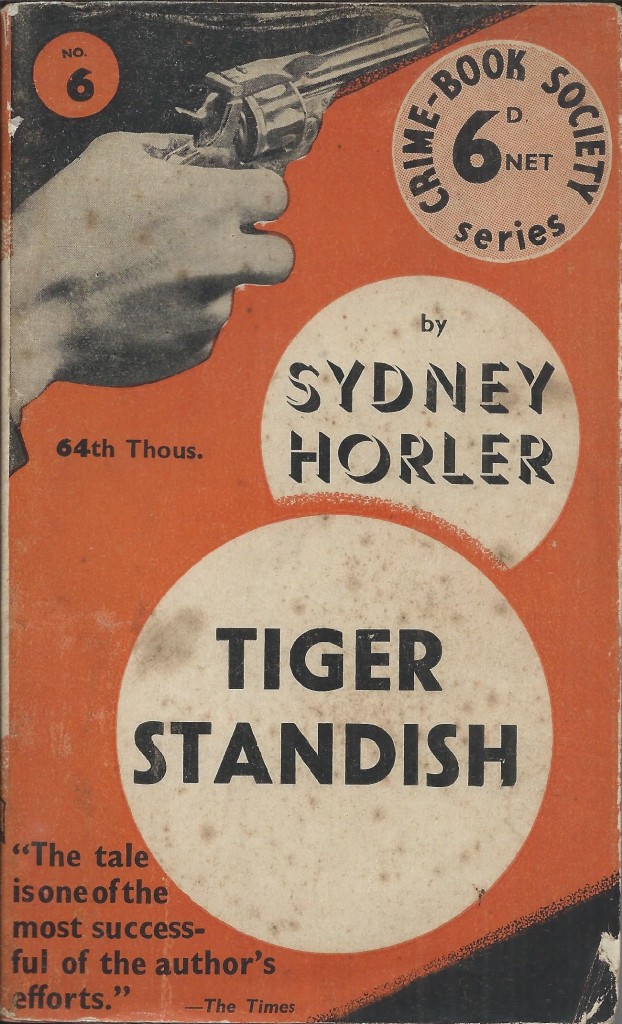

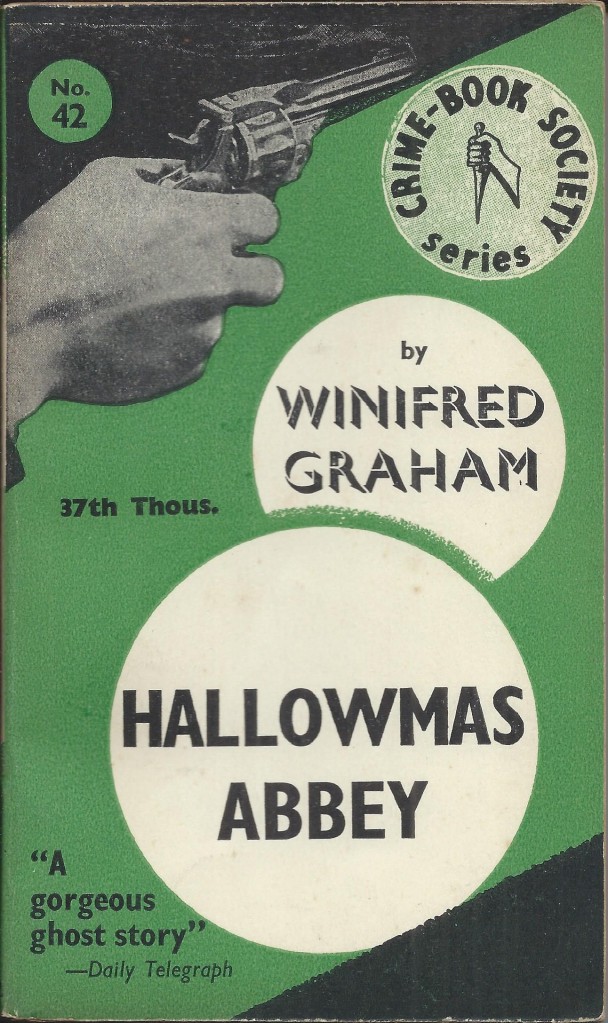

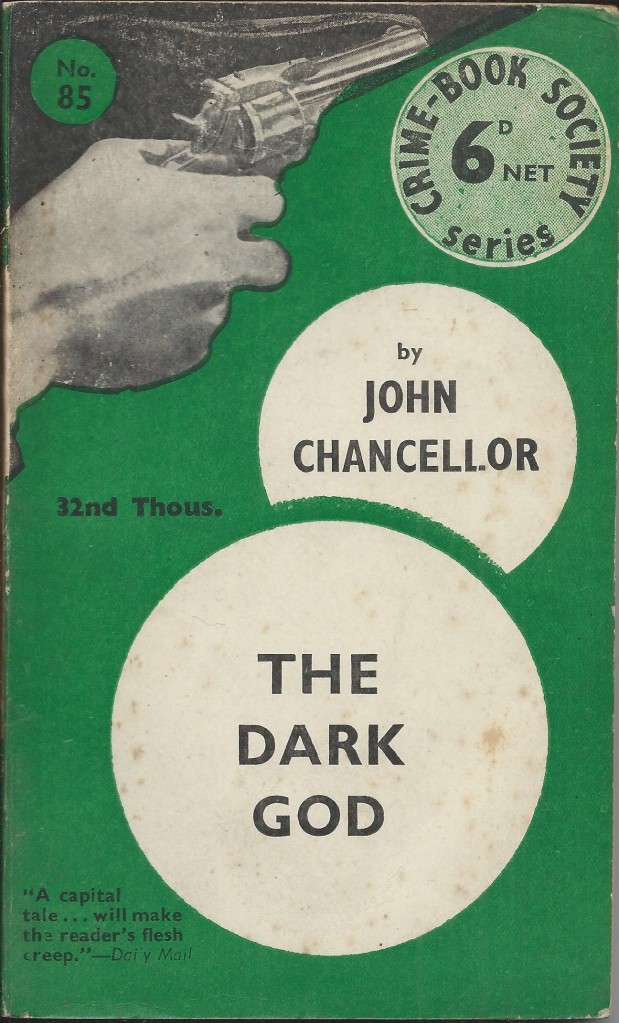

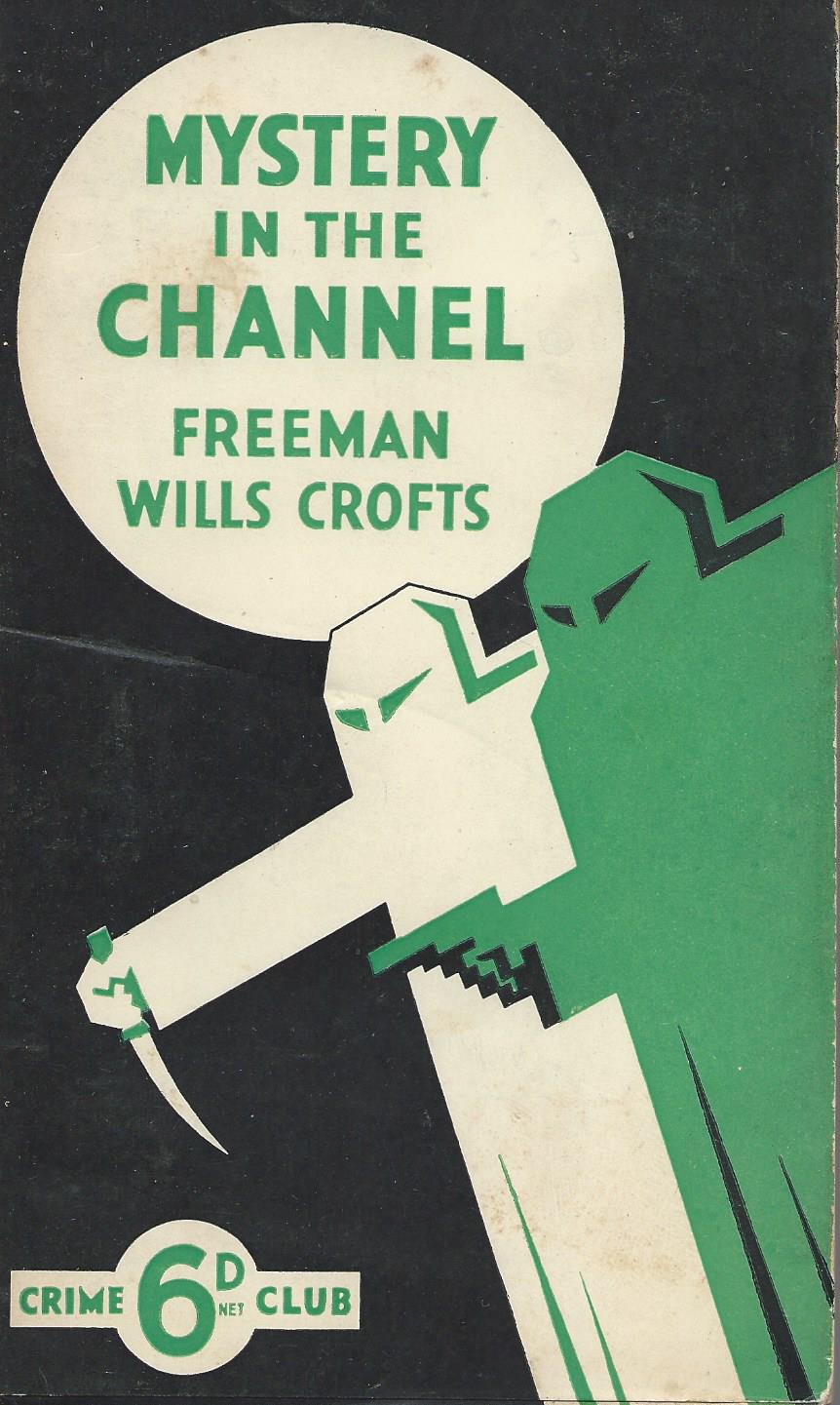

In June 1936, still less than a year after Penguin had started the Paperback Revolution, the Crime Book Society published its first paperbacks. This was again from the Hutchinson Group, but it was not so much a competitive response to Penguin, as a direct competitor for the Collins Crime Club paperbacks, launched in March 1936. At a time when crime novels were extraordinarily popular, Collins were the clear market leader, although they had allowed Penguin’s green crime titles to steal a march on them.

That Hutchinson saw Collins as their main competitor is clear first from the series name. Collins had their Crime Club series, so Hutchinson launched the Crime Book Society series. It was not a new name and had already been used for some hardback publications and had at least some structure of mailing lists, marketing and book selections, as the Crime Club did, but both were really book series rather than traditional clubs or societies.

It’s also very clear from the cover design. Collins had a stylised design with two masked figures holding a knife and a gun. Hutchinson opted for a single hand with a smoking gun as the main design, and a smaller hand with a dagger in the series panel and on the spine. Collins had the title and author name in a large white circle and the Crime Club logo in a small white circle. Hutchinson had the title and author name in two separate white circles and the logo and series number in smaller circles. On the dustwrappers, Hutchinson replaced the hand with a dagger with the 6d price, while Collins replaced the Crime Club logo with the 6d price.

It should be said though that it was not until a year or so later that Collins adopted ‘White Circle’ as an overall name for their various paperback series, so the use of white circles by Hutchinson was not as aggressive a marketing move as it might appear in retrospect.

Hutchinson also eventually settled on a very similar green to Collins for the colour of its covers, although it didn’t start off like that. The early titles come in a variety of colours, as used for Hutchinson’s Pocket Library, but from about volume 26 onwards they are all green. Green seems almost to have been adopted as an industry standard for paperback crime novels and gradually phased out for non-crime titles.

The one thing that Hutchinson couldn’t easily copy was the quality of authors represented in the Collins Crime Club. Where Collins had Agatha Christie, G.D.H. & M. Cole, Freeman Wills Crofts and John Rhode /Miles Burton, Hutchinson had Hugh Clevely, Seldon Truss and Grierson Dickson. Fine authors they may have been, but it has to be said that they have made little mark on literary history. Other largely forgotten authors in the series included Dawson Gratrix, Leo Grex and Peter Drax – what was it about surnames (or pseudonyms) ending in x?

On the other hand, Hutchinson did have Edgar Wallace and that was almost a guarantee of popularity and of sales. It points though to a suggestion that perhaps the Hutchinson list was biased more towards thrillers than pure detective stories. Collins tended to have a purist approach to crime novels, that treated them almost as puzzles, with appropriate clues for the reader to test himself or herself against the fictional detective. Thrillers, that prioritised excitement and fast-paced adventure, were for Collins a different type of novel, but Hutchinson don’t really seem to have had this distinction.

The first batch of eight titles published in June 1936 actually had quite a distinguished and well recognisable selection of authors, including Baroness Orczy, Eden Phillpotts and Sydney Horler alongside Edgar Wallace. But none of these are really known principally as crime writers in the Collins Crime Club sense, so again the focus seems more to be on thrillers. Some other titles later in the series look to be more like ghost or horror stories than simple crime.

Whatever the genre, the books must have sold relatively well, as the series prospered, or at least lengthened steadily. By the outbreak of war in September 1939 it had reached volume 67 and over the next few months the count increased to 81 by August 1940 and later to at least 85 before the numbering stopped. A few further titles were issued during the war, in a much slimmer wartime economy standard format, first with the price increased to 9d, and later to 1s 6d. Some of these later ones were shown as published by the Readers’ Library Publishing Company in association with Hutchinson, rather than directly by Hutchinson, but I suspect the difference is fairly small.

I know of one single Crime Book Society title published as a Services Edition, although there may well be others. Then after the war, the Crime Book Society seems to have gone back to being principally a hardback series, although a small number of the paperbacks were reprinted in a format very similar to the pre-war editions. These were again priced at 1s 6d, unnumbered, and treated as part of a combined reprint programme of pre-war Hutchinson paperbacks that included books from various series.

Leisure wares

Large publishing groups like HarperCollins, Penguin Random House or Hachette today use lots of different imprints for the books they publish. I’m not very sure why, because most readers would have little idea of the publisher’s name even after reading a book, never mind before buying it.

It wasn’t always so. Paperback series used to cultivate brand loyalty and the brand was very clearly signalled on the covers. If you bought a Penguin Book in the 1930s, 1940s or even later, you certainly knew it was a Penguin, both before you bought it and after you had read it. And given Penguin’s success, almost all other paperback publishers adopted clear and prominent brand identities as well. Which left Hutchinson, the HarperCollins of its day, with a problem. The Hutchinson Group contained a long list of publishing companies and it’s not clear to me how much cooperation there was between them. So they ended up with not one paperback series competing with Penguin, but several.

The Hutchinson Pocket Library was perhaps their flagship series in response to Penguin, but from different parts of the group also came Jarrolds Jackdaw books, Toucan books, John Long Four Square Thrillers and the Hutchinson Popular Pocket Library.

For several years in the late 1930s, the Leisure Library Company, another part of Hutchinson, resisted the trend to Penguinisation. They continued to publish paperbacks that were a throwback to pre-Penguin days – larger format, brightly illustrated covers, and selling for just 3d or 4d, substantially undercutting Penguin on price, but unashamedly down-market. Although Penguin mythology lauds the company for selling books at the low price of 6d, in reality Penguins were more at the top end of the paperback price range and only just below the 7d price of cheap hardbacks at the time.

But in 1940 the Leisure Library capitulated and joined the rush to establish Penguin-style paperback series, adding another to Hutchinson’s long list. Although in this case, it might be more accurate to describe them as Collins White Circle style.

Like Collins, the Leisure Library started separate sub-series for crime, westerns and romantic novels. Each sub-series had its own colour, with both companies using green for crime and yellow for westerns, and each added a stylised picture as part of the cover design.

To some extent also like Collins, the connection between the sub-series was not particularly emphasised, and the books were primarily branded as coming from ‘The Wild West Library’, ‘Crime Novel Library’ or ‘Romantic Novel Library’. The crime and romance novels are still shown as published by the Leisure Library Co. on the title page and the spine, but the westerns refer only to the Wild West Library. The westerns are though clearly linked to the crime novels by the square white title panel with perforated edges. These two series could almost have been called the Hutchinson White Square books, but oddly the Romance sub-series went for a white circle instead, making it easily confused with the Collins series.

The series was not very long-lived, although that was probably as much to do with the effect of the war on publishing, as with the commercial success or failure of the books. They were all published in 1940, in a relatively short period between about May and July, and few paperback series were able to maintain much of a publishing programme after that until the end of the war. There were a total of 32 books – fourteen crime, twelve westerns and six romances. I don’t think any of them have achieved much of a mark on literary history, even amongst fans of the relevant genres, but they added another layer to the story of the paperback revolution unleashed by Penguin.

A most English writer

The recent news of the death of Charles Aznavour reminded me, like many others, that this most French of singers, was born as Shahnour Vaghinag Aznavourian, the son of Armenian immigrants. To the British at least, he had an impeccably French accent, sang quintessentially French songs about French passions and in an unmistakably French way.

Which reminds me in turn of Michael Arlen, that most English of early twentieth century writers, who was though born as Dikran Kouyoumdjian, the son of Armenian immigrants to Britain. He himself was born in Bulgaria, but came to England with his parents in 1901 at the age of 5. He was sent to Malvern College, which no doubt turned him into the perfect English gentleman, as it no doubt still does for his modern equivalents. He remained a Bulgarian citizen though throughout the First World War (in which Bulgaria was aligned with Germany, Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire) becoming a British Citizen only in 1922 and changing his name at this point to Michael Arlen.

My interest in him is focused on the books he had published in Continental Europe by Tauchnitz and Albatross and in the UK by Penguin and Hutchinson. He first appeared as a Tauchnitz author in 1930, one of the new authors introduced by Max Christian Wegner, who had been appointed as General Manager of the company in 1929. The first of his books to appear was ‘Lily Christine’ as volume 4926. As usual Tauchnitz preferred to start by publishing his latest work, rather than going back to the earlier works that had made his name.

‘Lily Christine’, a tangled romance chronicling the lives of upper class society in the 1920s ‘Jazz Age’, had been published in the UK in 1928. It is probably fairly typical of the novels that led to Arlen being described as the English F. Scott Fitzgerald. The first printing in Tauchnitz is dated March 1930 at the top of the rear wrapper, and like all first printings from this era, has a two column list of latest volumes on the back and inside wrappers. Later printings have a single column listing on the back only.

It was followed shortly after by ‘Babes in the Wood’, a collection of short stories that begins with an apparently autobiographical story called ‘Confessions of a naturalised Englishman’ (although a note adds that all characters are fictitious, including the author). It appeared as volume 4943 and the first printing is dated June 1930 at the top of the rear wrapper. In the three months between publication of the two books, Tauchnitz had introduced a modernised design for the front wrappers, so that they look rather different at first.

A final Tauchnitz volume, ‘Men dislike women’ appeared the following year, as volume 5001, dated July 1931 on the rear wrapper. By this time Christian Wegner had been fired by Tauchnitz and was shortly to re-appear as one of the founders of the rival Albatross series. Albatross was hugely successful in persuading leading British and American authors to publish with them rather than Tauchnitz, and Arlen quickly switched allegiance to the new firm, no doubt partly because of his earlier relationship with Wegner.

‘Young men in love’, an earlier novel by Arlen, first published in 1927, appeared as volume 40 of the Albatross series in late 1932, in the blue covers used to identify love stories. Then in 1934, ‘Man’s mortality’, a rather different type of novel from his usual romances, was published as volume 211. This is more like science fiction, set 50 years in the future and often compared (almost always unfavourably) with Huxley’s ‘Brave New World’, published the previous year. Albatross gave it the yellow covers representing ‘psychological novels, essays etc.’, although perhaps slightly oddly ‘Brave New World’ had been given the orange covers of ‘tales and short stories, humorous and satirical works’.

Arlen’s third and final book in Albatross, was a book of short stories though, and so was given orange covers, making him one of only a handful of writers to have books published in Albatross in three different categories / colours (Evelyn Waugh, Aldous Huxley and Katherine Mansfield were others, and D.H. Lawrence managed four). ‘The Crooked Coronet’ was published in March 1938 as volume 362.

This was long after Albatross had taken over editorial control of Tauchnitz in 1934, with the two series being managed jointly from then on. Arlen could presumably have been published in either series, and the criteria for determining which series was used, are not entirely clear. Most authors stayed with the series they were published in before the two came together, generally with more of the edgier modern authors in Albatross and more of the longer established or more conservative authors in Tauchnitz. That fitted the harsh reality that authors banned by the Nazis could not be published by the German-based Tauchnitz. I don’t think that Michael Arlen was ever banned (or could ever be described as edgy and modern), so presumably he stayed in Albatross just because that was where he was at the time of the coming together.

Meanwhile in the UK, Penguin had been launched in 1935 and was buying up paperback rights where it could, mostly for books published several years earlier, rather than the latest novels. They obtained the rights to Michael Arlen’s ‘These charming people’, another collection of short stories that had been first published by Collins in 1923, and this appeared as volume 86 of the Penguin series in 1937. It includes a story called ‘When the nightingale sang in Berkeley Square’, a title that was later appropriated for a song that became one of the most popular songs of the second world war.

I think ‘These charming people’ was the only one of Michael Arlen’s works to appear in Penguin, but at least two others appeared in Hutchinson’s Pocket Library. Hutchinson was the original UK publisher for several of Arlen’s books, so they were in a stronger position to publish paperback editions in their series competing against Penguin. ‘Young men in love’ appeared as volume 50 of the series in May 1938 and ‘Lily Christine as volume 59 in October of the same year.

There may have been other paperback editions in other series, but by this time Arlen’s style was going out of fashion. He wrote mainly about an era and a society that had vanished, at least from public sympathy, with the depression of the 1930s and that was totally out of tune with the conditions of the second world war. For a few short years though he had been one of the most popular writers in Britain. His most successful novel, ‘The green hat’, first published in 1924, doesn’t seem to have ever appeared in paperback.

Arlen himself had left Britain in 1927, first joining D.H. Lawrence in Florence and then moving to Cannes, where he married a Greek Countess, Atalanta Mercati. He returned to Britain during the war, but then moved to the US for the last years of his life. His son, Michael J. Arlen, an American with Armenian / British / Greek / French / Bulgarian heritage, has written ‘Exiles’, a memoir of his parents and his childhood, itself published many years later in Penguin.

Hutchinson’s Famous Copyright Novels

Believe it or not, there were paperbacks in the UK before Penguin. There were even sixpenny paperbacks. There had been for a very long time and they were particularly plentiful in the first thirty years or so of the twentieth century, before Allen Lane came along to transform the market. Lane’s paperback revolution changed many things, perhaps most notably in getting rid of cover art, but also in changing the size of paperbacks. Before 1935, the standard size for a paperback was roughly 15 cm by 22 cm, or 6 inches by about 8.5 inches, considerably larger than the standard size ushered in by Penguin. What Penguin didn’t change was the price.

There were several long running series of these ‘large format’ paperbacks from publishers such as Hodder & Stoughton, George Newnes and Collins, as well as the series I want to look at here, from Hutchinson. They all looked fairly similar, all of course with cover art, mostly with advertising on the back and on other pages at the front and back as well, all on fairly cheap paper, usually priced at sixpence and often with the text arranged in two columns. That was probably a hangover from the story magazines that came before them that had a long history going back to Charles Dickens and ‘Household Words’ among others.

Frustratingly, another thing most of these books had in common was that they carried no printing dates and as a result there is a lot of confusion about when they were published. In some cases I have seen the same book described by dealers as being from ‘around 1900’ or from ‘the 1930s’, while having little idea which of them is more nearly correct.

Most of the series and most of the books have pretty much disappeared without trace. So far as I know almost nobody collects them or studies them and no libraries have significant holdings of them. There is far more interest in the Penguins and other similar books that replaced them. I can’t complain. That’s where most of my interest has been too.

The replacement happened incredibly quickly. The Hutchinson series of ‘Famous Copyright Novels’ had been running for many years and had reached over 300 titles when Penguin burst onto the scene in July 1935. By October of the same year, the series was dead and Hutchinson had launched a new series that copied Penguin in almost all material respects.

It’s hard to be sure when the Famous Copyright Novels series started, but my best guess is possibly 1924 or 1925. Volume number 2 in the series is ‘Life – and Erica’ by Gilbert Frankau, a book first published in 1924, so the series can’t be earlier than that. Most of the other titles were first published much earlier than this, as might be expected in a paperback reprint series, but I can’t identify any other early titles with a first printing date later than 1924.

If that’s the case, the series ran for around 10 years, from say 1925 to 1935. It had, for most of its life, a quite distinctive and striking appearance with primarily red covers, the title in yellow script and a cut-out style cover illustration with a white margin. Towards the end of the series that seems to have been altered, first to introduce a blue upper panel and then to move to fully illustrated covers with a much weaker series identity.

In other words, just as Penguin were about to launch one of the strongest and most successful attempts at series branding in paperback publishing history, Hutchinson were moving in the opposite direction. That didn’t go too well, then.

A high proportion of the books in the series are romantic novels, mixed in with adventure stories and thrillers. There are not many crime novels or westerns (Collins was the dominant publisher in these genres) and few books with any serious literary pretensions. The author most represented is Charles Garvice, an enormously popular writer of light romances, who on his own accounted for around 50 of the 300 plus titles in the series. Other popular authors included Charlotte M. Brame, Rafael Sabatini, Kathlyn Rhodes, William Le Queux, E.W. Savi and Rider Haggard.

Hutchinson was a sprawling group of associated publishing companies, which each retained some separate identity, and at least one of these, Hurst & Blackett, published a very similar series. Hurst & Blackett’s Famous Copyright Library at 6d a volume seems to have included titles from almost exactly the same authors, although I have not seen a copy of any of them.

Printers’ Pie – the Hutchinson years

‘Printers’ Pie’ had started in the early years of the twentieth century as a way to raise funds for a Printers’ charity. It continued until at least 1918, sometimes twice a year, with Christmas issues called ‘Winter’s Pie’, but stopped publication soon after. There may have been one or two publications in the 1920s called the ‘Sketchbook and Printers’ Pie’, but information is scarce.

In 1935 it was revived (see this earlier blog post) to raise money for the King George’s Jubilee Trust and then for other charities, now using the titles ‘Christmas Pie’ and ‘Summer Pie’. So far as I can tell the final issue in this series, published by Odhams, was in 1939.

But then after a gap of three or four years, it appeared again in 1943 under the original title, this time published by Hutchinson. The publication marked Walter Hutchinson becoming Festival President of the Printers’ Pension, Almshouse and Orphan Asylum Corporation, the original charity for which ‘Printers’ Pie’ had been created, and was to raise funds for them.

It was now in a small paperback format, and selling for the relatively high price of 2s 6d. Pre-war issues had sold for 6d and in 1943 most paperbacks were selling for around 9d. But as well as being for charity, this was on unusually good quality paper for a wartime publication, featured a colour cover and several pages of glossy photographs in two sections. There were stories by H.E. Bates, Howard Spring, L.A.G. Strong and James Hilton among others.

It was followed by ‘Christmas Pie’ at the end of 1943 in a similar format, again selling for 2s 6d. This time there was an appeal for donations to the same Printers’ charity, but no direct mention that the proceeds or profits from the publication would go to the charity. Most issues from then onwards contained no mention of being for charity, but on the other hand the price came down to 1s 6d. The exceptions were the Spring Pies for 1945 and 1946, with the price raised to 2 shillings and profits going first to the Bookbinders’ Cottage Homes and Pensions Society, and then to Toc H.

The format instead seemed just to be adopted by Hutchinson as part of their series of Hutchinson Pocket Specials. From Autumn 1944, there were more or less regular issues five times a year, titled as Spring Pie, Summer Pie, Autumn Pie, Winter Pie and Christmas Pie, published roughly in March, June, September, November and December.

Each issue had a colour portrait of a girl on the cover and inside a mix of articles, short stories, cartoons and photographs. mostly in a light-hearted tone. The style feels very similar to ‘Lilliput’, then a popular monthly magazine.

In April 1946 there was an extra issue called Pie’s Film Book, with Vivien Leigh on the cover as Cleopatra, from one of the big films of the year. It was printed entirely on glossy paper, lavishly illustrated with black and white photos of film stars, and selling at two shillings. Pie’s Film Book No. 2 appeared the following year in similar format, with Margaret Lockwood on the cover, but that seems to have been the end of this venture.

There were other attempts to modernise the format. Colour appeared internally for the first time in the Christmas 1947 issue, with four reproductions of Dutch paintings and in 1948 many of the black and white photographs were replaced by colour illustrations of various kinds. But perhaps it was still not modern enough for the post-war world. The Summer and Christmas issues of 1948 experimented with some discreet nudity, but it was too late or too desperate.

So far as I know, the 1948 Christmas issue was the last until it reappeared in a slightly larger format and at the reduced price of one shilling in December 1949 as ‘Winter Pie’. The editor is now shown as Barbara Vise and the cover illustration is by (presumably related) Jenetta Vise. Inside there’s no longer any colour, but the layout looks less cramped. The content though is less than riveting, featuring articles such as ‘Why I like going to the cinema’ by the Bishop of London, alongside articles on suits of armour and portrait miniatures.

It was followed by ‘Spring Pie’ in April 1950 in a similar format, although this time with a centrefold featuring colour photographs of pottery and porcelain. But then this too seems to have died.

After that, Hutchinson seem to have given up any ambitions to continue the series. Both the ‘Pie’ title and the aim of raising money for good causes seem to have passed back to Odhams, the publisher of the pre-war issues. They published at least one more issue in 1952 in the larger pre-war format, as ‘Summer Pie, in aid of the National Advertising Benevolent Society. That may well have been the last of the Pies.

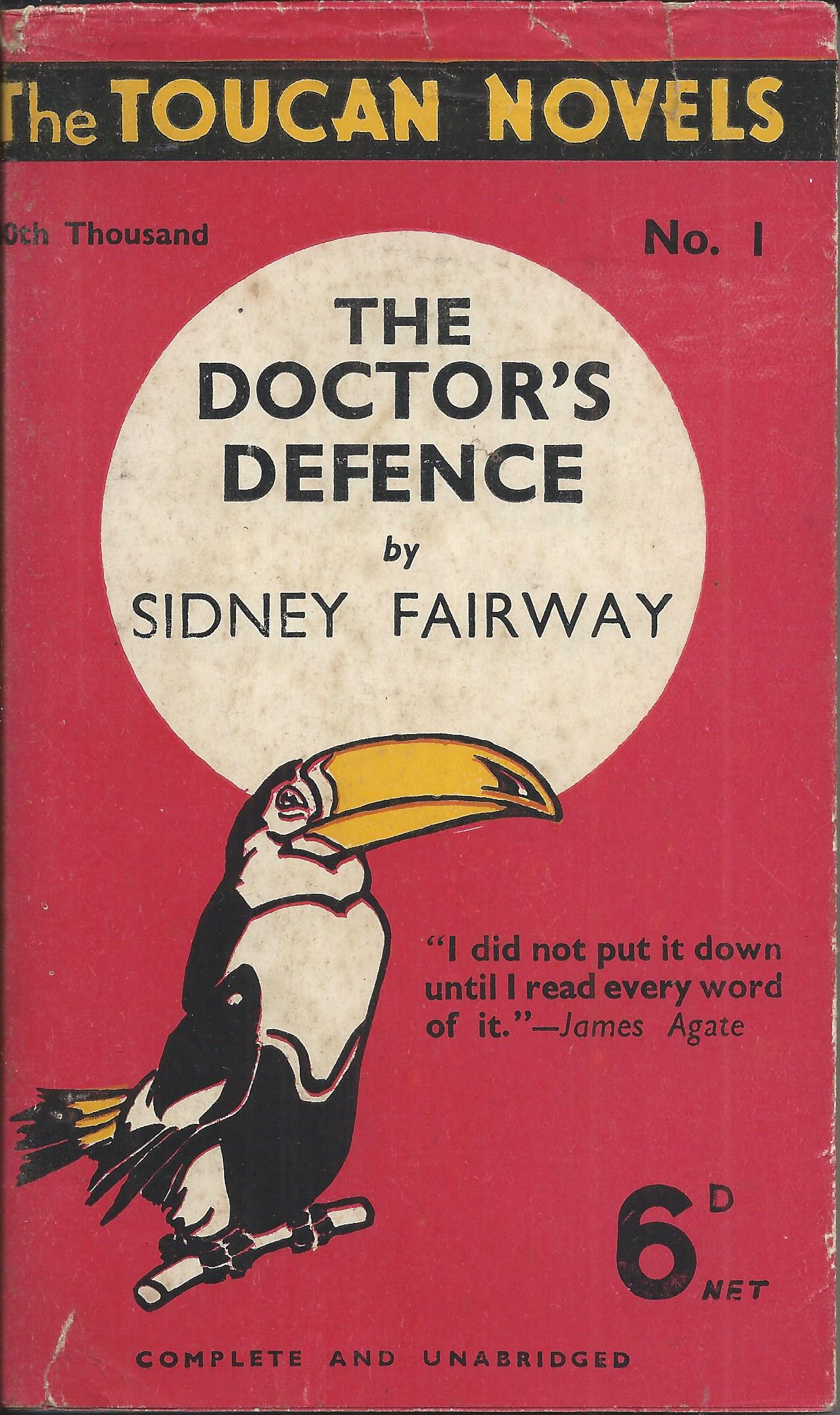

Just think what Toucan do

Having recently written a post about the Jarrold’s Jackdaw Library, it seems appropriate to follow it up with one about the Toucan novels. The two series seem to go together in several ways. They both came from the Hutchinson group of publishers, and they share a physical similarity, not only with each other, but with almost all the new paperback series launched in those few years after Penguin’s breakthrough. They also share, with each other and with Collins, the use of a white circle as the main title panel.

And of course they both use a bird as their brand and series title. They were far from the only series to do so in the period after the launch of Penguin Books.

Toucans and Jackdaws – birds of a feather

In choosing a Toucan as their brand, Hutchinson may have had one eye on Penguin and on Jackdaw, but they probably had the other eye on Guinness, whose famous toucan had appeared just two years earlier. What would previously have been a rather obscure bird, had been propelled to the centre of media attention by the Guinness advertising campaign.

In reviewing Jackdaw, I asked the question why Hutchinson needed another paperback series in October 1936. At that point they already had the Hutchinson Pocket Library, the Hutchinson Popular Pocket Library and the Crime Book Society series, all launched within the previous 12 months. So it’s even more strange that just 4 months later they launched yet another new series and another new brand. Was there really a market space left for the Toucan Novels when they appeared in February 1937?

I can’t work out whether it was a deliberate strategy not to put all their eggs in one basket, or just a lack of strategic co-ordination within the group.

Other Hutchinson 6d series from 1935 / 1936

Toucan at least showed some evidence of co-ordination, as the books came from several different publishing imprints within the Hutchinson Group. Most of the first group of titles came from Hurst & Blackett, although there were two from Hutchinson itself. Then a group of books from Stanley Paul and another from John Long. But like Jackdaw, and like several other new paperback series in the 1930s, there was then a pause after an initial rush of titles. It took time for the market to adjust to yet another new paperback series, and time for the initial print run to sell out.

After volume 20 appeared in June 1937, there were no new titles for almost a year, then a small group of titles in summer 1938, but it was not until May 1939 that the series really got going again. The main publisher in this second phase was Stanley Paul, although there were also books from Hurst & Blackett and a few from Skeffington & Son.

The covers of the early books were printed in two colours to highlight the Toucan’s yellow beak, and most of the early books were in a purply crimson colour, with a few in green. The group of books from volumes 17 to 20, all published by John Long, are missing the yellow highlighting on the book covers, although it is still there on the dust-wrappers. Was this an economy measure, saving on two colour printing in a place where it would not normally be noticed by the purchaser? Or was it just a mistake?

Front cover and dust-wrapper of volume 17

It turned out, perhaps inadvertently, to be a herald of the future. From around volume 32 onwards, possibly earlier, all or almost all books were printed with yellow covers. This allowed the toucan’s beak to be yellow without the need for two-colour printing, although it did lose some of the earlier impact. A little while later, dust-wrappers were dropped, and then prices started to creep up, with some volumes selling for a while at 7d, before wartime economy measures really started to bite.

An early Toucan in green and a later one in yellow

By mid 1940 it was impossible to continue on anything like the pre-war basis, and the numbered series came to an end with volume 62. A few more books were published during the war, effectively as one-offs, but they had to meet the war economy standard, which meant low paper quality, small fonts and small margins, making the most of the paper rationing that was hitting all publishers. I know of two wartime Toucans at 9d, although there may well be others. Then later, at least three books at 1s 3d, and post-war others at 1s 6d.

The books published in the Toucan series had no great literary pretensions, and few of them are much remembered today. The authors are generally pretty obscure, although there is one Edgar Wallace title and perhaps most significantly, two of the Maigret books by Georges Simenon. Simenon was at that time so little known in Britain that he had to be described on the book cover as ‘The Edgar Wallace of France’.

As a final comment, seven books in the Hutchinson Group series of Services Editions were also referred to as Toucan Novels in a brief mention at the top of the cover. It’s not entirely clear what the point of this was, as there was no other Toucan branding, and only one of the books had previously appeared as a Toucan novel. Indeed three were from a publisher, Rich and Cowan, which had not previously contributed books to the Toucan series. But it’s one of many examples of confusion in branding within the Hutchinson Group at that time.