Monthly Archives: July 2019

US Penguins 1945 – 1948

Where I left the story in my last post (US Penguins 1942 – 1945), Ian Ballantine had left the business to help found Bantam Books. For a period, Allen Lane sent Eunice Frost out to New York to work with Kurt Enoch, probably not just to help him out, but to keep an eye on him.

That was only ever a temporary measure – Eunice Frost was too valuable back at Head Office – but Lane had his eye on a longer term solution. He had made contact with Victor Weybright, an American with publishing experience who had been working at the American Embassy in London during the war.

Allen Lane needed someone to act as a balance to Kurt Enoch, whom he no longer fully trusted. Enoch had taken the business a long way away from the founding principles of Penguin, competing head-to-head with Pocket Books, Dell Books and others on their terms, rather than trying to change the market. US Penguins had adopted illustrated covers on US style glossy card and the standard size of other local competitors. And the quality of the list was arguably not consistent with Penguin’s UK positioning either.

But Enoch had a personal stake in the capital of the US business and as he had organised the capital raising, some of the rest was held by his friends and associates. So both Allen Lane and Victor Weybright had to tread carefully at first.

Lane’s policy seems to have been one of constructive ambiguity – sending Weybright out more or less to negotiate his own way into the business. When he arrived, Enoch claimed not to have heard of him and was unwilling to meet him. After a two hour wait outside a closed door, there followed a week of talks mostly conducted through lawyers. The story is told from Weybright’s point of view in his autobiography, although this is highly self-serving and may not be entirely reliable.

But in the end an agreement was reached, which Weybright characterised as ‘absolute parity’ for the two men in terms of status within the organisation. Enoch would concentrate on production and distribution and Weybright on the publishing programme and public relations, an area where he considered Enoch’s abilities extremely limited. Perhaps surprisingly after such a difficult start, they formed an effective partnership that not only stayed together for many years, but was highly successful in a very competitive market. Enoch initially saw Weybright simply as a stooge for Allen Lane, but it was not long before the two of them were united in negotiating a break from Lane and from Penguin Books.

It’s hard to know exactly when Weybright’s influence began to be seen in terms of the series itself. He arrived in August 1945, but probably had little effect on the books published in the following few months. They included notably ‘Trouble in July’ by Erskine Caldwell, an author not approved of by Lane, but who became enormously important for the business over the following years.

Weybright almost certainly though was influential in the major changes that took place from January 1946 and included a significant redesign in the look and feel of the books, as well as the launch of a non-fiction Pelican list. Both were important developments that had long-lasting effects, but I’ll leave discussion of the US Pelican list for another day.

In some ways the re-design was just another step in the gradual transition that had been going on for three to four years already, away from the UK Penguin style and towards fully illustrated covers. It introduced full colour printing and illustrations stretching right across the front cover, and perhaps even more symbolically, it abandoned the colour-coding that had been such a key part of the Penguin brand, in favour of a bizarre system of different shaped symbols to indicate genre. The changes could be seen as the final break with the sober traditions of Penguin in the UK.

But in another way the business was actually moving back towards some of the key Penguin attributes in the UK. In particular the size of the books changed back to the standard UK size, distinguishing them from most other US paperbacks. And although not immediately apparent (perhaps not even to Allen Lane), the nature of the list was changing to one that was maybe more in line with Penguin principles.

From a list that throughout most of 1944 and 1945 had been dominated by crime novels and relatively light fiction, there were now indications of more serious literature. D.H. Lawrence and E.M. Forster appeared in the January 1946 list, Virginia Woolf, Jack London, Sherwood Anderson and John Steinbeck over the next few months, and then in July, three plays by Bernard Shaw were issued to mark Shaw’s 90th birthday. Weybright was diplomatically taking some of the best of Penguin’s output from the UK and mixing it with more specifically American titles.

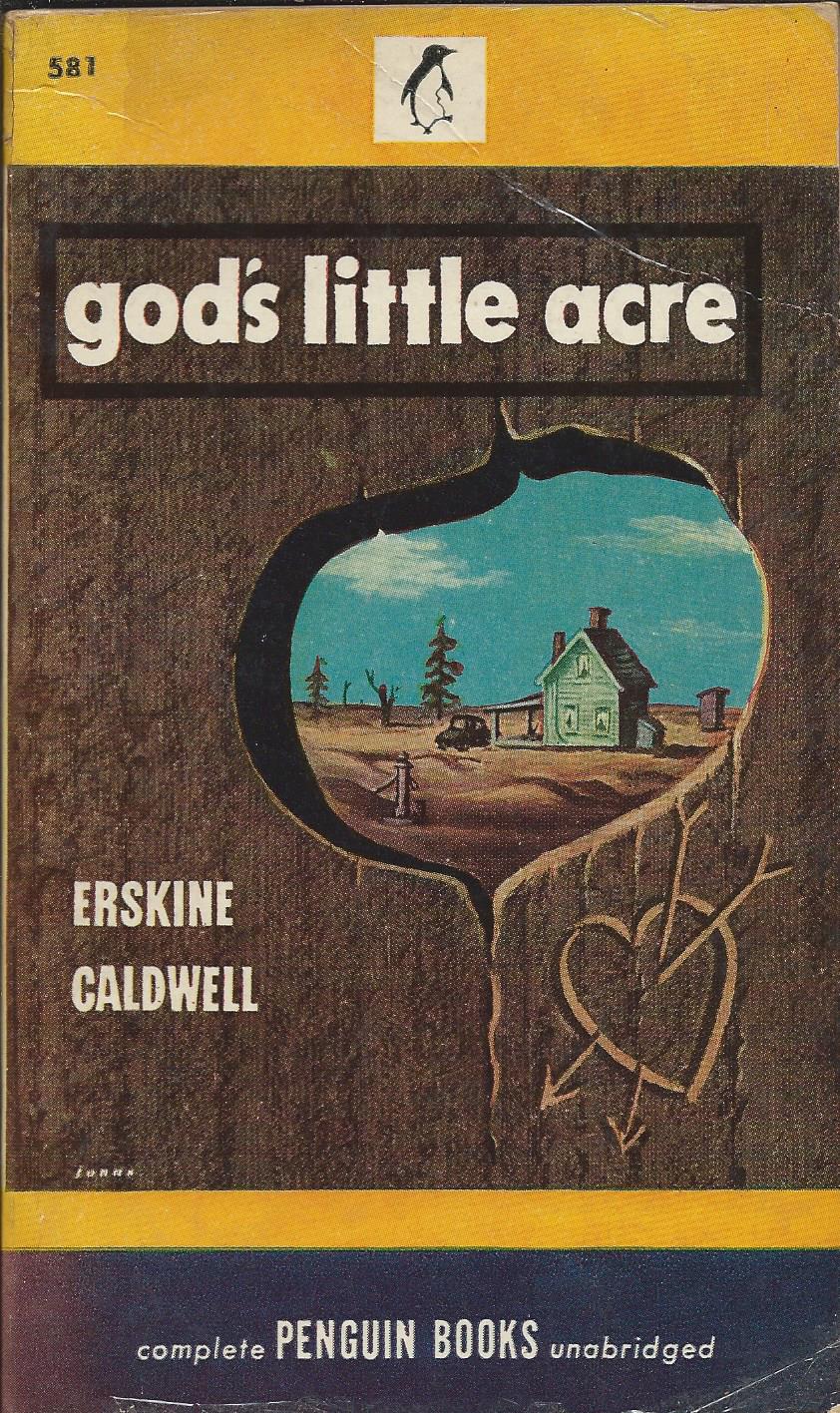

There were still plenty of lighter novels, and several that were too racy for Allen Lane’s taste. Weybright records that Lane seemed annoyed by the fact that Erskine Caldwell’s ‘God’s Little Acre’ was a runaway success, supporting the business through a difficult time. But the proportion of crime stories certainly went down and there does seem to have been a serious attempt to position the series as rather more up-market and literary. Indeed I’d suggest that the 80 or so books published in 1946 and 1947 stand comparison with almost any run of 80 books appearing in the UK Penguin main series.

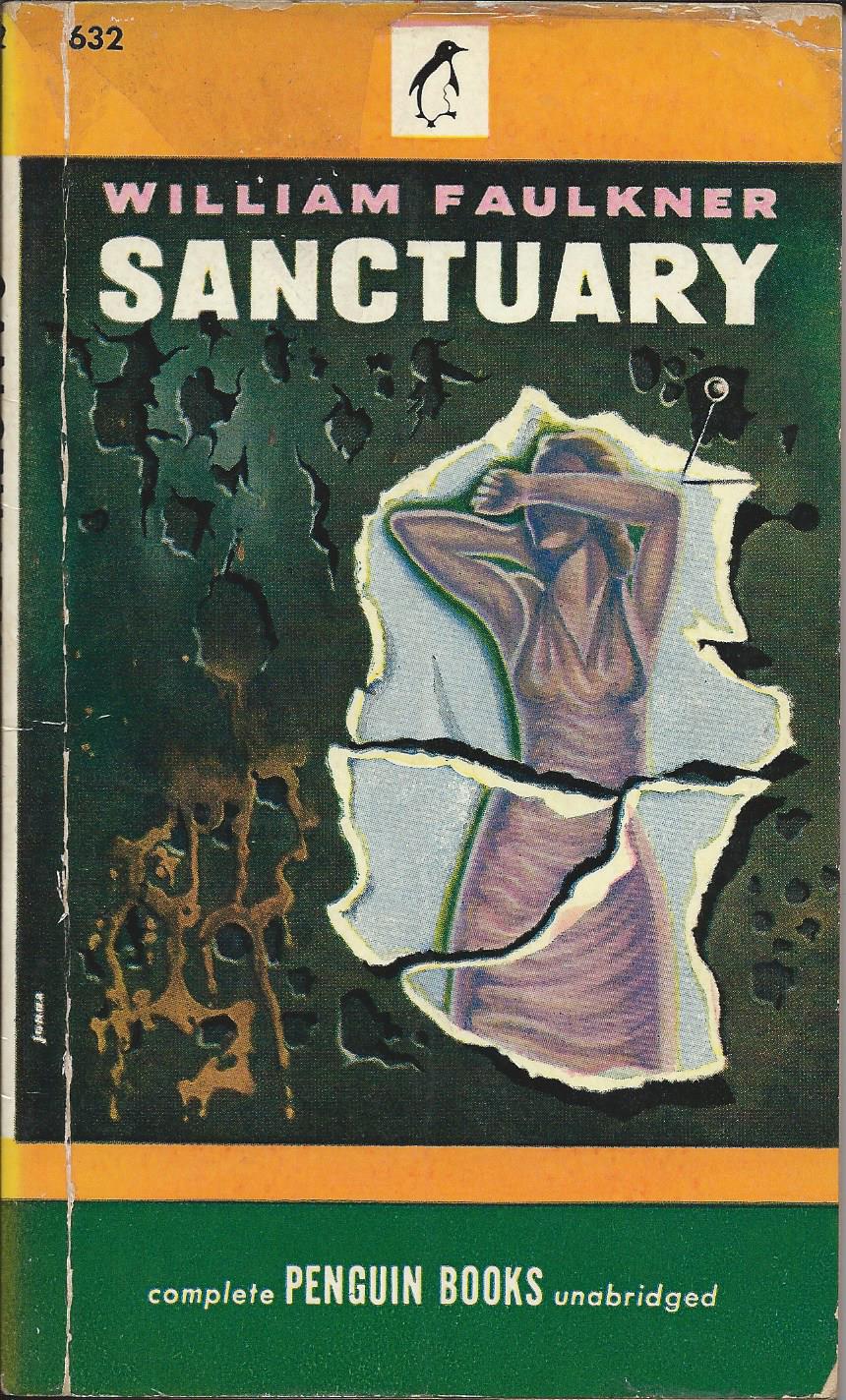

In September 1946 Lady Chatterley’s Lover appeared as volume 610 and it was followed in November by E.V. Rieu’s new translation of ‘The Odyssey’ published by Penguin in the UK. Early 1947 saw Henry James and Joseph Conrad added to the list followed by William Faulkner’s ‘Sanctuary’. Lane disapproved of Faulkner, but when he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1949, Weybright must have felt vindicated, as indeed when Lane later fought a court battle to publish Lady Chatterley in the UK.

Of course part of Allen Lane’s disapproval stemmed from the illustrated covers rather than the actual contents of the books. The covers were undoubtedly becoming more colourful and striking (regarded by Weybright as a necessity to compete in the US market), but Lane’s generalised slur on illustrated covers as nothing but ‘bosoms and bottoms’ would not have been a fair description of them, at least in 1946/1947.

Most of the covers were designed by Robert Jonas, often featuring stylised images evoking the spirit of the books rather than specific scenes from them. The Jonas covers are often described as having a distinctive style, but in fact several of the covers by other artists seem to me to be consistent with them, so it may be more of a house style influenced by Jonas rather than just the style of one artist.

When Allen Lane visited New York in April 1947 it became clear that a split with the UK business was inevitable. The terms were negotiated in October of that year and by February 1948 the changes were under way. Penguins were to be re-branded as Signet Books, while Pelicans became Mentor Books – the overall business becoming the New American Library. For a period in early 1948 books were branded as ‘Penguin Signet’ but from August 1948 references to Penguin were dropped and the business was on its own.

Freed of UK constraints, the cover art took another turn. Robert Jonas was for a time Art Director, but from about November 1947 his stylised designs started to give way to a more brash style of which Allen Lane would certainly not have approved. Penguins had come a long way in a relatively short time.

US Penguins 1942 – 1945

Penguin’s attempt to woo the American market had started in 1939 with the establishment of an office in New York under the twenty-three year old Ian Ballantine, importing Penguins from the UK. It was not a great time though to be shipping books across the Atlantic and by 1941 it was clear that the operation had no future unless books could be produced locally.

A small number of UK books were reprinted in the US, but to extend the operation and move into local publishing, Allen Lane would need a more experienced publisher. He was perhaps lucky to find Kurt Enoch, one of the founders of Albatross Books, and a Jew who had been forced by the Nazis to leave Germany and then subsequently had had to flee for a second time from Paris, after it fell to the German army ( for the full story, see ‘A strange bird’ by Michele Troy).

Enoch had recently arrived in the US, was looking for work, and suggested to Lane that he could raise the capital to launch a local publishing programme. Lane took him on as Vice President responsible for production and design, with Ballantine in charge of distribution / sales. That leaves it a little unclear who was responsible for the core function of choosing and commissioning new titles. Enoch was the one with experience in this area at the time, so presumably took the lead, although Ballantine later went on to become a hugely successful publisher in his own right.

Albatross Books had been in many ways the model for Penguin, so Allen Lane might reasonably have expected to find in Kurt Enoch somebody who shared his ideals and vision for the business. But from the start Enoch seems to have had doubts about key parts of the Penguin brand that had been so successful in the UK.

Penguin’s UK launch had been almost an overnight success and had transformed the UK paperback market, with almost all competitors adopting the main elements of the Penguin ‘package’ – size, price, colour coding, dustwrappers and so on, but above all, no cover illustration. The first tentative steps in the US market had not triggered any similar revolution and Enoch seems to have been sceptical that it ever could. Almost from day one, he seems to have had his eye on illustrated covers.

For Allen Lane and others back in Harmondsworth though, this was an article of faith. Before Penguin’s UK launch, there had been plenty of people saying that non-illustrated covers could never work in the UK market and they had proved them all wrong. Now they saw the brightly striped and immediately recognisable covers of Penguin Books as their main weapon in conquering new markets. The scene was set for a struggle that could have profound consequences for Penguin’s future.

In early 1942 the new US Penguin series launched, with numbers starting from 501. The first two books, numbers 501 and 502, appeared with the iconic striped covers. First blood to the Brits. But by volume 503 the design had changed significantly to one that allowed space on the front for a brief written description of the book, and on the back for advertising or for information about the author. Enoch must have been planning this for some time, perhaps waiting for approval from Head Office.

While Lane may not have been happy with any move away from the classic design, this change looks as though it may have been deliberately designed to get approval. It retains enough elements of Penguin identity to still look Penguin-ish and it’s still a very restrained design that doesn’t introduce any illustration to the front cover. It also retains the principle of colour coding used in the UK. Crime is still green, although perhaps strangely, the classic Penguin orange for novels is replaced by red, and yellow is more widely used for a range of books including non-fiction and westerns.

But this was by no means the limit of Enoch’s ambitions. He wanted cover illustration, and as it happened he had the right opportunity to get a foot into the door. A short series of classic texts illustrated by woodcuts had appeared in the UK in 1938 as Penguin Illustrated Classics. They had used illustration on the covers and had included ‘Walden’ by Thoreau, an American classic that would fit well into the new US Penguin series. How could the UK Head Office possibly object to a cover illustration that they had themselves used? The book appeared as volume 508 and was the first American Penguin to feature cover art.

Once the principle had been breached, Enoch was not going to let go. He had shown how a simple illustration could (not coincidentally?) fit well into the cover design he had introduced and others would follow. The first was ‘Tombstone’ by Walter Noble Burns, volume 514 published in October 1942, and from then on illustrated covers were the norm. It may have grated even more in the UK that the process started with a western – at this stage considered too down market for Penguin in the UK, although later on in the series, a few did appear.

The first illustrations were quite small, but it was not long before they were taking up the entire panel. And in the meantime, Enoch was attacking another of Penguin’s key brand attributes – the size of the books. Penguins had always been roughly 11 cm by 18 cm, a format based on the golden ratio and again copied from Albatross. But paperbacks in the US and particularly those from the main competitor, Pocket Books, were shorter and squatter. So Penguin moved in line with them.

This was in November 1943, barely 18 months after the launch and already Penguins had little in common with their UK parents and looked more like the local competitors. Even the glossy card covers and the red page edges looked more American than British. Any idea of changing the market had been abandoned. It was the Penguins that were having to change.

From late 1943 onwards, the rate of new titles started to increase and the cover illustrations became more and more dominant, with the single colour of the covers increasingly used within the picture as well. From volume 566 in October 1945, a second colour is used on the cover before moving on to full colour shortly afterwards.

This was though another turbulent period for the business. Some time around the end of 1944 or the beginning of 1945, Ian Ballantine resigned to work on the launch of a competitor, Bantam Books. He had learned what he could from Enoch and was ready to take the next step in his publishing career. Allen Lane however was not prepared to leave Kurt Enoch in sole charge of Penguin’s US business. Eunice Frost, originally Allen Lane’s secretary and still in her twenties, but in practice one of his closest aides in London, was sent out to New York to hold the fort, while Lane attempted to make more permanent arrangements.

That eventually led to the appointment of Victor Weybright to work with Enoch, and to a whole series of other developments. I’ll come back to them in another post and also look separately at the US Penguin Specials, an important series in their own right, which had been published alongside the main series throughout the period I’ve been talking about.