Category Archives: Theatre

Imperium and A Christmas Carol

The RSC are giving Shakespeare a rest this Christmas. While the main theatre has its usual family-friendly show with David Edgar’s adaptation of ‘A Christmas Carol’, the Swan Theatre hosts Imperium – Mike Poulton’s adaptation of Robert Harris’s Cicero novels. At over 6 hours of theatre, spread over two shows, this one is perhaps a little less family-friendly. But it has three long books to cover, not just a slim volume of Dickens.

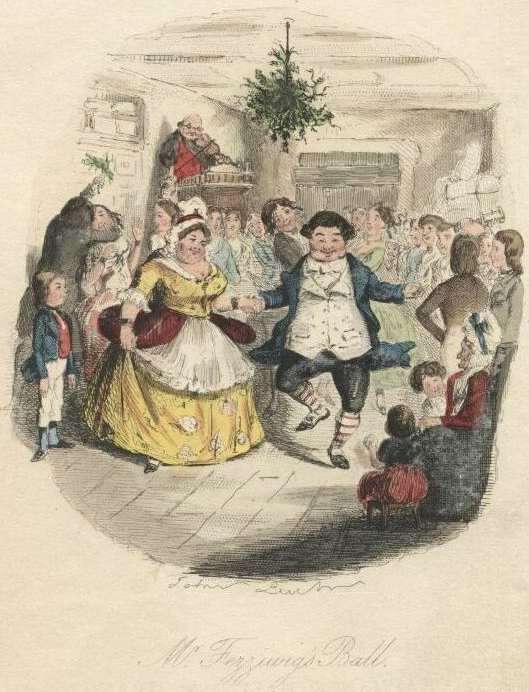

‘A Christmas Carol’ is of course a treat, and particularly a visual treat, although not because of lavish scenery. At times it needs only a top hat and a dress coat here, a couple of doors there, to summon up Victorian London, or perhaps more specifically Dickensian London. The scene with Mr. Fezziwig in Scrooge’s youth is probably not really Victorian, but captured so perfectly the Dickensian image of a slightly earlier period that it seemed to bring the original book illustration to life.

Phil Davis is well cast as Scrooge, surely partly on the basis of his earlier role as Smallweed in the TV adaptation of Bleak House. I didn’t find his personal journey to greater empathy and happiness entirely convincing though. There’s neither a gradual process of understanding, nor a sudden epiphany – more just a feeling of well yes, of course I see that, which is difficult to square with his earlier attitudes.

But the bigger difficulty I have with this production is the role of Dickens, who wanders in and out of the action with his friend, and later biographer, John Forster. David Edgar and the Director, Rachel Kavanaugh, seem to have decided that the story doesn’t stand well enough on its own. It risks being seen as – well, a feel-good family-friendly Christmas show. So they rather ram down our throats the message that Dickens was not just writing a Christmas ghost story – he was a campaigner trying to draw attention to some of the social evils of the time. Slightly bizarrely they show Forster having to convince Dickens, the great storyteller, that a story might be the best way to get his political and social message across.

But in doing so they seem to be denying this very premise. They don’t trust the storyteller to get his message across through the story – they have to give him a second chance to air his views by talking directly to the audience as well. Dickens didn’t have to do that – he could just publish the story and let it stand on its own – and the RSC shouldn’t need to either.

‘Imperium’ too has a narrator, who both takes part in the action and stands back from it to pass comment on it, but at least here it’s a device that comes directly from the book. Joseph Kloska plays Tiro, Cicero’s secretary and biographer. He’s very likeable in the role, although it’s slightly odd that he seems not to age, while his master does. The role works much better than with Dickens in a Christmas Carol, and partly because it’s treated a little less earnestly and more tongue in cheek.

There’s still a feeling though that the RSC isn’t quite prepared to trust its audience to draw their own conclusions. As one example, at a key point in the first play they plant in the audience’s mind the idea that perhaps it was Cicero himself who wrote some forged letters. They then reinforce the idea with muttering from one of his slaves about the role he had to play in the affair. But that’s not enough – at the end of the play, as though delivering the final coup, they reveal that, surprise surprise, Cicero wrote the letters.

It felt similar in the second play when Mark Anthony’s continual drunken staggering seemed mainly designed to reinforce the point, repeated several times, that his wife was the real power behind the throne. A few lines of carefully crafted dialogue, or perhaps even a single raised finger, could have made the point far more effectively. Or given that the plays were very light on female roles, we could perhaps have heard more directly from Fulvia herself, with less focus on her alleged puppet (compare Shakespeare’s treatment of Lady Macbeth for example). As it is, the women in the play are little more than caricatures, there for sentimentality or for cheap jokes about licentiousness or avarice.

And what on earth was going on with the apparent appearance of Julius Caesar’s ghost, screaming ‘Avenge me’, at his state funeral? Were Mark Anthony’s words not enough indication that were those who would be seeking revenge? I don’t recall Shakespeare having to make the point quite so unsubtly. Subtlety was not really the strong point of this version, certainly not when it came to a perma-tanned, bouffant-haired Pompey declaring “I’m a Republican”.

Perhaps I protest too much. No-one is claiming that this is Shakespeare. For all the lack of subtlety, these were two wonderfully enjoyable evenings of theatre. Richard McCabe held them together with a strong performance as Cicero and impressive stamina, channelling his inner Tony Hancock into moments of world-weary cynicism inbetween his oratorical triumphs and disasters. I enjoyed too the performance of Peter de Jersey as Julius Caesar, convincing both as a military leader and as a smooth politician, where you could always sense the steel hand beneath his velvet glove.

Henry V at Stratford

My mental image of Henry V, assembled more from references elsewhere than from actually seeing it, was of a stirring tale of English valour against the odds – a very patriotic, even nationalist play and certainly a very serious one. ‘Once more unto the breach, dear friends’, and the St. Crispin’s Day speech are so much a part of our culture that they define the play if you’re not familiar with it.

So it was bit of a shock to discover that the play itself, at least in this production, is almost more a knockabout comedy than a tale of heroism, or a reflection on the nature of war. Getting the balance right between the two seemed difficult to me, and I wasn’t sure that the RSC quite managed it. If Bardolph, Nym and Pistol, brought over from Henry IV, were the only comic characters it would be fine, but we have another comedy set up with a Scotsman, Welshman and Irishman, a comic scene in the French court where the Princess is trying to learn English, another with one of the King’s soldiers (Williams) who ends up striking him, and even in the more serious scenes, the French Dauphin seems to be treated largely as a comic character.

With all that going on, the transition from comedy to stirring speeches, or to the King’s introspection, seems crucial. How do you deal with a comedy Scotsman, followed by an order from the King to kill the French prisoners? Some of the comedy was brilliantly done – assuming it’s still OK in the 21st century to mock the Scots, the Welsh, the Irish and the French through stereotypes, in a manner that certainly wouldn’t be OK for some other nationalities. Some of the serious stuff was brilliantly done too, and Alex Hassall carried off the title role well – entirely convincing in the transition from Prince Hal in Henry IV to the warrior king here. He delivered the stirring speeches well, looked the part of a heroic leader, but still convinced in the more introspective speeches and in his bumbling courtship of the French princess.

I also enjoyed the staging, which made good use of the thrust stage, but seemed much simpler in terms of scenery or props than most RSC productions. That made sense of Oliver Ford Davies’ role as the Chorus, powerfully urging us to use our imaginations. Sometimes there are so many visual flourishes at the RSC that imagination is hardly required.

But I wasn’t entirely sure that the transition from comedy to seriousness worked so well. The English (or British?) army was presented as such a ragbag bunch of misfits that its conversion to a supreme fighting force capable of defeating an army several times its size, seemed little short of a miracle. If it was King Henry’s oratory that did the trick, it wasn’t obvious here. His passionately delivered ‘What’s he that wishes so?’ speech, seemed to be met with a sullen silence. If Chris Robshaw’s inspirational words to his team were met with that kind of reaction, then it’s no wonder that England are out of the Rugby World Cup.

Othello – RSC at Stratford

Plenty of interest and some very good performances in this production of Othello at Stratford. Some of the effects and the choices by the Director, Iqbal Khan, worked really well, others I was less sure about. The stand out performance was from Lucian Msamati as an unrepentant Iago, whose laugh as the lights went down at the end of the play was spinechilling. That he’s a black actor needn’t have been important – he wasn’t playing a role in which skin colour is really significant – but Khan chooses to make it important, using it almost to set the tone for the production, emphasising racist elements and changing the dynamic with Othello, and particularly with Cassio.

In the scene where Iago conspires to get Cassio drunk and violent, the production seemed to move a long way away from Shakespeare, with Iago singing (beautifully) an African folk song and Cassio taking part in a rap contest, that reveals him as a closet racist. That Iago should resent his black commander promoting a less experienced and racist white man above him made some sense, but it made less sense of the position of Othello, who in a multi-racial army was no longer the outsider, himself the obvious victim of racism. It was also hard to see Othello as ‘the noble Moor’ when he’s portrayed as both complicit in torture and not above using it himself on Iago – so hardly noble, even without considering whether he’s a Moor or not.

Hugh Quarshie as Othello turns suddenly to jealousy and to violence in a powerful scene that makes some sense of what is to come, but is less obviously connected to what went before. This is a sudden eruption of the green-eyed monster, not a slow-burning build up. Was violence just under the surface, coming from his background as a military commander, more than as an outsider?

Iago on the other hand, is allowed to build some sympathy with the audience that makes it difficult for much of the play to see him as the personification of evil. He’s more of a good-natured rogue, closer to Sid James than the Borgias until his scheming reaches its tragic climax and that chilling laugh breaks out. Throughout though there’s little sympathy with his wife in a relationship that is put into stark contrast with the relationship between Othello and Desdemona.

As usual, the RSC made good use of its versatile stage, here filling a central section with water, used in the first scene as a Venetian canal, and later as a bathing pool for Desdemona. A grille rose and fell to expose the water, cover it over with a platform or even double as a table. We’re used to spectacular effects in modern theatre, but I know nowhere else that’s as innovative and adaptable in its use of space as the RSC on its Stratford stage.

The setting and costumes were quite difficult to pin down . Much of it appeared to be present day, with echoes of Iraq in the images of torture, faffing around with aerials to improve laptop connections, and one speech delivered as if through video-conferencing. Some of the costumes though, particularly for the women, and some of the other design elements, seemed much more traditional. But despite any small quibbles, this was a thoroughly enjoyable evening and another success for the RSC.

The Father at Theatre Royal, Bath

Spoiler alert – this review contains significant plot and production details, which you might prefer not to know until after you’ve seen the play. If you have a chance though, do go to see it.

This is not at all a comfortable play. You simply never know quite what’s going on. Almost all the basic details of the situation laid out in the opening scene, are contradicted in later scenes and many of the contradictions are never resolved. We don’t know whose flat we’re in, whether the daughter is in London or in Paris, whether she’s married or divorced, whether her husband / partner is sympathetic or menacing, what has happened to a second daughter, and so on. The same roles are played by different actors in different scenes. so we don’t even fully get a grip on who’s who. Time is a fairly slippery concept too as scenes are interrupted or replayed, so we never really have a full grasp of time, place or person – fairly basic concepts in theatre. The music between scenes becomes increasingly fractured and the furnishings gradually disappear from the set.

The aim of all this disorientation is to show life from the point of view of the father, who is gradually slipping into dementia and reverting to childhood. He’s not sure who his daughter is, who the carer is, or where he is. Everything keeps changing to the point that he questions everyone else’s sanity as much as his own. It’s a convincing performance from Kenneth Cranham as the father, who wanders around the stage in pyjamas a lot of the time, making little sense of what’s going on, before ending up in a hospital bed, desperately calling out for his mummy. Claire Skinnner plays his daughter (for most of the play!), which inevitably brought to mind the same actress trying to deal with both an ageing father and young children in ‘Outnumbered’, as well as some of the parallels with ‘King Lear’.

In a Question and Answer session with the cast after the performance, one audience member suggested that absence of love was the tragedy of the play, but that didn’t feel right to me. There was little doubting the love that Claire Skinner showed in her portrayal of the daughter, but love isn’t always enough in the tragedy of old age. As I’ve seen with my own parents and others, the role of carer can be particularly thankless and another questioner almost broke down as she thanked the cast for their sympathetic portrayal of this. But in the end that wasn’t really the point either. This was about the tragedy of the parent, through whose eyes we were being asked to experience it, rather than that of the carer. It succeeded brilliantly in portraying that, leaving all of us just a little bit more nervous about what might be to come, particularly those of us who are maybe closer to the high risk age than we might like to imagine.

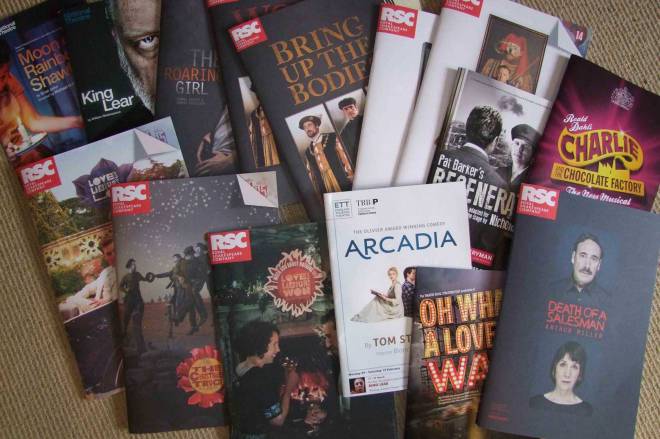

A glorious year of theatre

Sue and I agreed at the end of March last year that we would go to the theatre at least once a month for the next year. I don’t think I’ve ever managed that before in my life, but we’ve now achieved it and it’s been a glorious year. There are links below to my reviews of each play, but overall we’ve seen some wonderful theatre and some outstanding performances.

Certainly it helps that we’re close enough to visit Stratford regularly, and we’re rarely disappointed by anything we see at the RSC. I’ve enjoyed visiting the theatre there for many years, but it seems to me to go from strength to strength. The new stage is just brilliant and a massive vindication of all the effort that went into transforming the theatre and the associated fundraising. One of the most striking observations for me over the year has been how restricting the proscenium arch stages in other theatres are in comparison with the thrust stage at Stratford. It’s given huge freedom to the directors there and they’ve seized the opportunity with both hands. Even the highest priced seats at other theatres can sometimes offer a view that’s disappointing in comparison with the cheapest seats at Stratford. We sat in the Upper Circle last week and had a fantastic view of a production that was constantly entertaining as well as thought-provoking. The quality of acting and of speaking is invariably high, from the leading actors down to the smallest part, there’s almost always live music to support the productions, the sets and the costumes are beautifully done and the overall standard of production is superb.

When we’ve strayed further afield though we’ve found plenty to delight us. Three very enjoyable trips to the Theatre Royal in Bath and one to the Everyman in Cheltenham to see touring productions, and two fantastic productions at the National in London. If what we’ve seen over the last year is at all representative of the current standard of theatre in Britain, then it’s in rude health.

So what were the highlights? In terms of individual performances, seeing Anthony Sher play both Falstaff and Willy Loman has been hard to beat, although Simon Russell Beale as King Lear may have run him close. In terms of productions, it’s even harder to choose. ‘Great Britain’ at the National Theatre was certainly a highlight, as was Sher’s ‘Death of a Salesman’, but overall I’m not sure there was anything I enjoyed more than the combination of ‘Love’s Labour’s Lost’ and ‘Much ado about Nothing’ played with a single cast and a single setting at Stratford. Not Shakespeare’s finest plays, and not played with a stellar cast, but both of them a visual delight, beautifully produced, directed, acted and spoken and hugely entertaining throughout.

The other question then is what next? The year may be finished, but the appetite has only been whetted, and I hope to see many more plays over the next twelve months and beyond. Maybe a bit less obsessively scheduled as at least one every month, but still regularly seen, and if I can manage it, still regularly reviewed on this blog.

Full list of plays seen with links to the reviews

Moon on a rainbow shawl (Errol John) – Theatre Royal, Bath

King Lear (Shakespeare) – National Theatre, London

The roaring girl (Decker & Middleton) – Swan Theatre, Stratford

Wolf Hall & Bring up the bodies (Poulton / Mantel) – Aldwych Theatre, London

Great Britain (Richard Bean) – National Theatre, London

Henry IV Part I (Shakespeare) – Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Stratford

Henry IV Part II (Shakespeare) – Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Stratford

Regeneration (Barker / Wright) – Everyman Theatre, Cheltenham

Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (Roald Dahl et al) – Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, London

Love’s Labour’s Lost (Shakespeare) – Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Stratford

The Christmas Truce (Phil Porter) – Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Stratford

Much ado about Nothing (Shakespeare) – Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Stratford

Arcadia (Tom Stoppard) – Theatre Royal, Bath

Oh what a lovely war (Joan Littlewood et al) – Theatre Royal, Bath

Death of a Salesman (Arthur Miller) – Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Stratford

Death of a Salesman – The RSC in Stratford

Perhaps an unusual play to take over the main stage in Stratford, normally devoted to the works of Shakespeare at this time of year, but ‘Death of a salesman’ comes with a huge reputation as one of the best and most significant plays of the 20th century. If it’s a gamble by the RSCs Artistic Director, Gregory Doran, to put on a non-Shakespeare production, then being able to call on Anthony Sher and Harriet Walter to star in it, must reduce the risk a lot, and he has ended up with a wonderful success to justify his decision.

Anthony Sher gives a great performance as washed up salesman Willy Loman, entirely convincing as his mood swings between buoyant optimism and suicidal depression. I’ve never seen the play before so I can’t compare him against other actors, and it’s clearly a great part to get your teeth into, but I thought it was a stunning performance. Harriet Walter has a less meaty part as his wife, but was the perfect foil, having to deal with his constantly changing moods, but always supportive, understanding his character better then he does himself and entreating their sons to make allowances for him.

As always the RSC produced a great ensemble performance, making dynamic use of the thrust stage, and the swings in time and setting as well as mood were well handled. I particularly liked the transformation from a domestic scene to an outdoor one as actors rose standing still from below and then suddenly switched into action to create the criss-crossing bustle of the city streets.

Alex Hassell, having played Prince Hal to Sher’s Falstaff earlier in the year in Henry IV, produces another good performance as Biff. He seems to be the RSC’s rising star, slated to play Henry V as well in the autumn, and as with Henry, here he has to play both the older Biff and his younger self, which doesn’t look easy to carry off. There’s not the same growth and maturing that there is with Prince Hal, as Biff seems to be stuck in a pattern of petty theft. But he too achieves some kind of maturity with his realisation that he may be better off working outside, even if it means giving up on the American dream that his father and his brother Happy (well played by Sam Marks) still seem enthralled by.

Oh, Oh, Oh what a lovely war!

There’s been no shortage of World War I plays recently. After seeing Regeneration in October, followed by ‘The Christmas Truce’ in December, we’ve now been to see the grand-daddy of them all – ‘Oh what a lovely war’ at the Theatre Royal, Bath in a production by Terry Johnson that comes from Stratford East, where it was originally created in 1963.

At least with this play there’s no doubt where it stands, and there’s none of the risk of over-sentimentality that hung over ‘The Christmas Truce’. The shocking statistics of the war are regularly run on an electronic ticker tape across the stage and despite the jauntiness implicit in staging it as a music hall show, it’s always a subversive jauntiness ready to undermine any hint of patriotism, sentimentality or sanctimoniousness with a vulgar comment or a hard statistic.

It probably seemed much more subversive in 1963 than it does now. The image of lions led by donkeys has since become the standard view of the First World War, and we have no difficulty in imagining that the officer class were callous and out of touch, or that businessmen were profiteering from the war. But the bigger difference may be that a good half of the audience then would have had personal memories of the war, as well as familiarity with the music hall tradition and all the old songs. Now it’s in danger of appearing like a quaint period piece, rather than a biting satire, despite efforts to maintain its relevance that included a reference to donkeys that cut to a picture of Nigel Farage, and an interruption to the curtain calls to remind us that the ‘game of war’ is still being played.

There was plenty to like in the production, with some strong acting, great singing, some very funny scenes and the occasional emotional tug. I thought some of the scenes with the pierrots rather lacked energy, but there was plenty of vitality elsewhere. The incomprehensible sergeant major was a great laugh, as was the incomprehension between the French and British generals, and the stylised football game between Germans and Brits worked rather better than the real kick-about on stage in ‘The Christmas Truce’.

Tom Stoppard’s Arcadia by the English Touring Theatre

‘Arcadia’ by Tom Stoppard is billed as a comedy, and there are certainly some very funny lines, but it’s also a drama that’s about as serious as it gets. It helps to have a reasonable understanding of the implications of chaos theory and the second law of thermodynamics, not to mention garden design history, the life of Byron and mathematical iteration. I’m not a specialist in any of those, so it’s a challenging play that makes you think a lot.

The structure of the play is well worked, going back and forth between scenes in the early nineteenth century and the late twentieth century, interweaving the past and the present in a way that reminded me strongly of ‘Possession’ by A.S. Byatt, one of my favourite books. Since ‘Possession’ appeared in 1990 and this play in 1993, it’s hard to believe that Stoppard wasn’t influenced by the novel. Like Byatt he throws in a fair bit of satire on modern academics, but he has larger scientific themes as well. Thomasina, a girl in the 19th century, presumed to be talking before the second law of thermodynamics had been formulated, illustrates the principle by discussing how jam can be stirred into a rice pudding, but can’t then be unstirred. Meanwhile the 20th century academics, trying to recreate what happened in the past, seem engaged in trying (unsuccessfully) to put the rice pudding back together.

We saw the play in Bath in a production by the English Touring Theatre. It worked well enough, and gave us a very stimulating night in the theatre, but I wasn’t entirely convinced by some of the acting and particularly the delivery of some of the lines. When you’ve got lines to deliver that can be difficult to understand, the director and the actors need to help the audience by varying the pace, the emphasis, the timing, the gestures, to bring out as much meaning as possible. This is what the RSC is often superb at doing. They take words written 400 years ago and bring out the meaning, or often bring out new meaning, by the way they deliver the lines, so that it sounds much more up to date. Here we had up to date words, that were at times made to sound as if they were written 400 years ago, so little did the delivery aid understanding.

Having said that, there were some good performances, and I thought one of the best came from Ed MacArthur, playing Valentine Coverley in his professional stage debut. His conversations with Flora Montgomery as Hannah Jarvis, worked well, but I was less convinced by Wilf Scolding’s portrayal of Septimus Hodge. We had to imagine he was not only a tutor coping with the tricky questions of a precocious student, but also a friend of Byron’s and a habitual seducer as well, which for me required too much suspension of disbelief. He threw his lines off too glibly as though he was Oscar Wilde delivering aphorisms, and it was difficult to take his relationship with Ezra Chater at all seriously. I suppose we’re not meant to do so, if Chater is just a comic character, but that requires a tricky balance between the serious and the comic to pull off, and for me it just didn’t work.

Much Ado about Nothing – or Love’s Labours Won

Are the RSC right that ‘Much ado about nothing’ was once known as ‘Love’s Labours Won’, the title they’re using for this production? I’m happy to leave that to the Shakespeare scholars. I didn’t feel they made a particularly strong case here for any direct Shakespearean link between the two plays, but they created plenty of links of their own, through set design, music, casting and costume. All these aspects succeeded marvellously in ‘Love’s Labours Lost’ and they’re no less successful here. The two productions taken together are a gloriously exuberant experience, whether or not there’s a lost link between them.

Perhaps more than anything I loved the set design, by Simon Higlett, with scenes sliding in and out and up and down, all directly based on nearby Charlecote Park. A billiards table rises up from below, for Don John and Borachio to play on while plotting the downfall of the lovers; an entire chapel slides in from the back for the wedding scene, the drawing room dominated by a massive Christmas tree comes in and out repeatedly, and the family tomb rises and falls for Claudio to mourn at. To complete the visual effect, the men change from khaki battledress to bright red military dress jackets, to white tie and tails and then to long overcoats and homburg hats, while Michelle Terry as Beatrice starts as a World War I nurse before working her way through an entire wardrobe of Twenties costumes. The overall effect is stunning, with every scene almost posed as a tableau.

In pursuit of the perfect image, of course the Director, Christopher Luscombe, takes some liberties with the play. The initial pretence that the stately home has been converted to a military hospital, with Beatrice and Hero as nurses, lasts no longer than necessary to show off the costumes and establish the link with ‘Love’s Labour’s Lost’ (and ‘The Christmas Truce’) before they’re into other costumes and enjoying a house party – a slightly odd one too, in which characters dressed as servants dance freely with the guests. The scene where Benedick overhears the conversation staged for his benefit, is then played (brilliantly) as pure farce. Indeed the leading characters spend so much time playing for laughs that it’s a little hard to take them seriously in the tragedy of the chapel scene. And the introduction of a Christmas carol at the start of the second act seems little more than sentimentality.

Overall though the music is another strength of the production, as indeed is the standard of acting from a strong cast. I wasn’t entirely sure about the casting of Don Pedro, who seemed an unlikely rival suitor for Hero, and at one point veered dangerously close to looking and sounding like Bobby Ball playing Lee Mack’s Dad in ‘Not going out’. But Michelle Terry and Edward Bennett are excellent in the lead roles and I enjoyed David Horovitch’s performance as Leonato.

If it leads to performances like this, I’m happy for the RSC to call the play anything it wants.