The Crime Club goes paperback

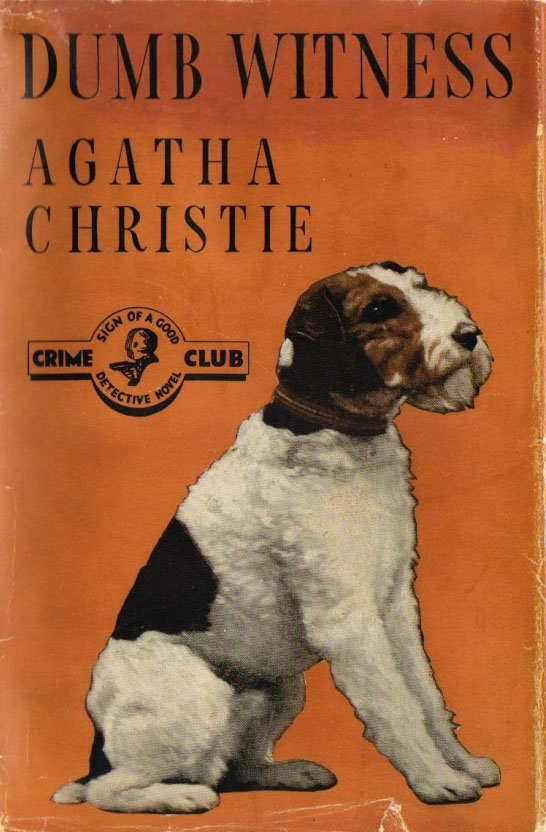

Launched in May 1930, the Collins Crime Club had been a huge success, surfing the wave of public interest in the golden age of detective fiction. By 1936 it had published around 200 titles and claimed to have around 20,000 subscribers, although it was not really a club – just a mailing list of potentially interested readers. The star writer was undoubtedly Agatha Christie, but there was a wide range of other writers including John Rhode, Freeman Wills Crofts. Philip Macdonald and G.D.H & M. Cole.

The books sold at 7 shillings and sixpence, a fairly standard price for UK hardbacks at the time, but one that put them out of the price range of most ordinary people, who perhaps borrowed them through libraries or waited for cheap editions to be published. A selection of the books was published in cheaper paperback editions in continental Europe through Albatross Books, with which Collins were associated. The Albatross Crime Club published only books from the Collins Crime Club, in distinctive red and black covers, but these could not be imported into the UK.

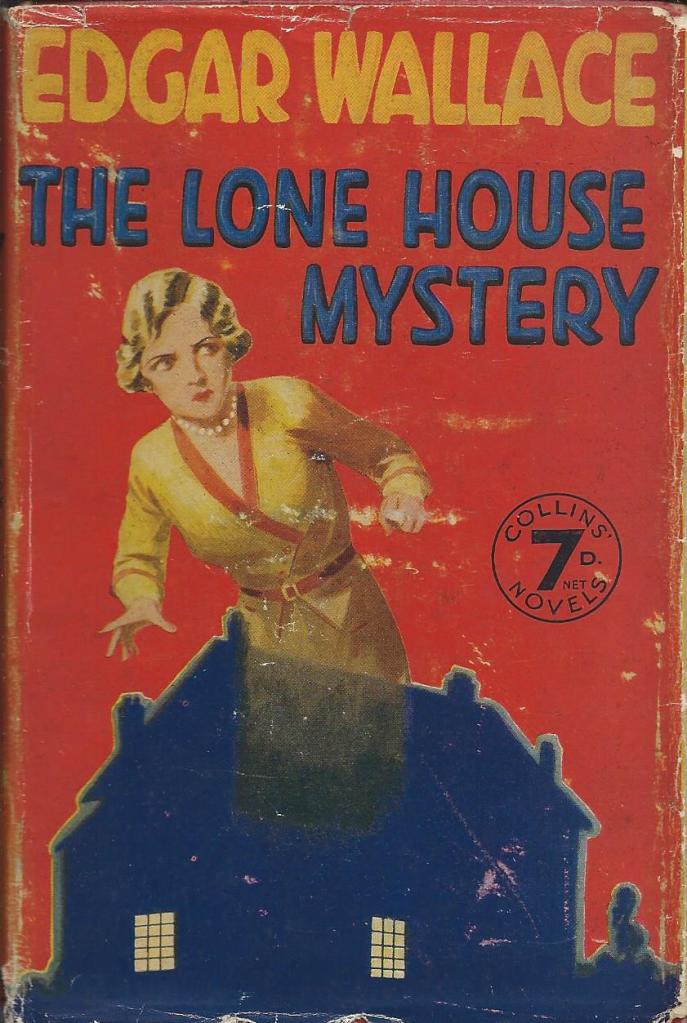

It was the success of Albatross in Europe that gave Allen Lane the idea for Penguin Books. Possibly Collins should have seen it coming, but they were experimenting in a rather different direction in the UK at the time, with a series of cheap hardbacks sold at 7d, less than 10% of the standard hardback price. This series certainly included crime novels, although I am unsure whether any of the titles had previously appeared in the Crime Club.

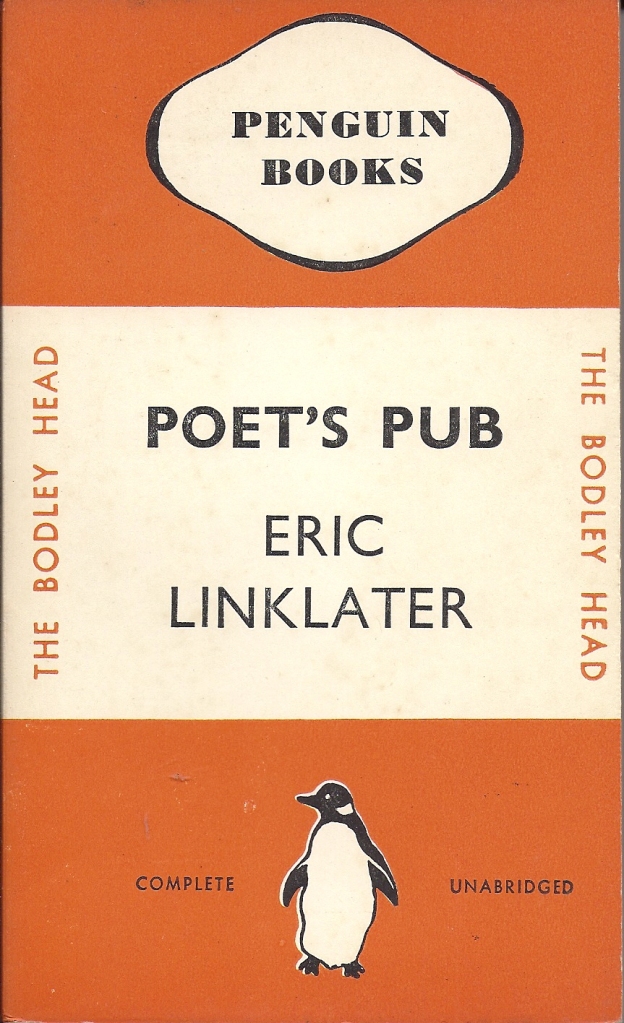

Quite why hardbacks at sevenpence were a failure, while Penguin’s paperbacks at sixpence were a roaring success is hard to say, but they were. Penguin’s launch in July 1935 was transformational. Within months, perhaps even weeks, it was clear that their format was a success. By October, Hutchinson had launched their own paperback series in a very similar format to Penguin, and a new market had been established.

Collins could see now that Penguin represented a threat to their core market. There had been only a handful of crime novels in the early titles, but enough to warn them of what could happen. In fact Penguin had issued what almost amounted to a direct challenge to Collins by including a novel by Agatha Christie in their first ten titles. ‘The mysterious affair at Styles’ was the first of Christie’s novels and like her other early novels had been first published by The Bodley Head, before she moved to Collins in 1926.

The Bodley Head was the Lane family company that Allen Lane worked for up to the launch of Penguin, so this was a book he had access to, or at least thought he did. As it happened, a copyright dispute over ‘The mysterious affair at Styles’ led to Penguin withdrawing it a few months later and replacing it with another early Christie novel ‘The murder on the links’, but the episode made clear that Penguin’s ambitions included becoming a major publisher of paperback crime.

So Collins were now fighting a rear-guard action as they started to plan a paperback series of Crime Club novels. Some aspects were almost a given. The price would be 6d, the size would be the Albatross and Penguin size (using the golden ratio) and the books would have a dustwrapper in the same design as the cover. These were basic features of the market established by Penguin.

But the most important feature of the Penguin revolution was no cover illustrations, other than a standard logo. This feature, again copied from Albatross, seemed fundamental to Penguin’s success. It conveyed an image of seriousness and established a break with the traditions of earlier paperbacks, which had often had lurid cover illustrations. For the Collins Crime Club, cover illustrations had been an important part of their marketing, so it was a big decision to replace them with a standard designed cover.

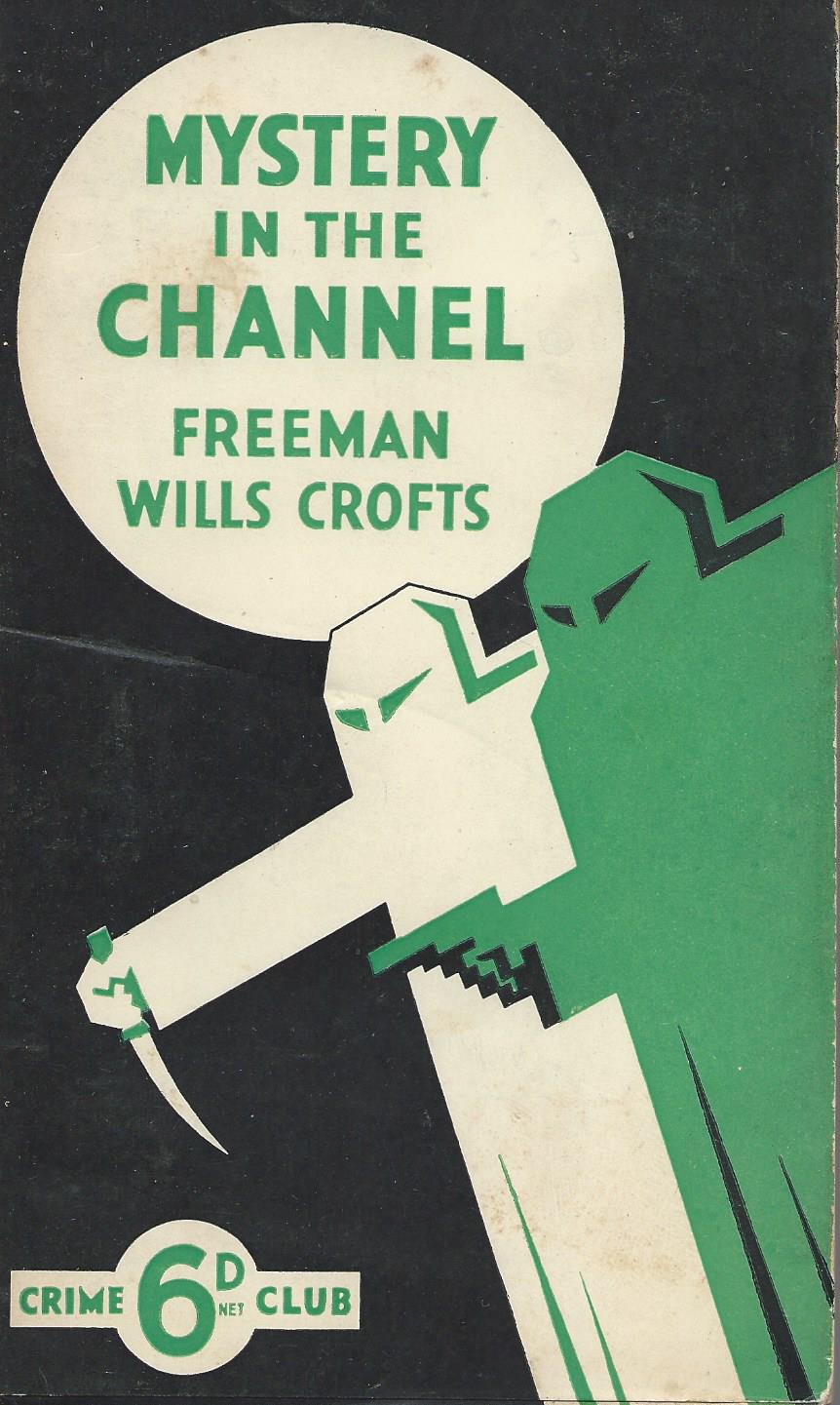

In the end, Collins settled for a new design that created a standard identity for the series and established its up-market credentials, while still having a nod to the earlier Crime Club branding. It was sufficiently similar to the Penguin format to make clear that it was a direct competitor, but sufficiently different to be instantly recognisable as a Collins Crime Club novel.

Instead of Penguin’s central white band, Collins introduced a large white circle for the title and author. And as well as using colour to indicate genre (again green for crime), Collins splashed across the cover a stylised picture of two masked murderers carrying a pistol and a knife that was effectively a development of the original Crime Club branding.

In its own way this cover was as classic a design as was Penguin’s three bands, and indeed it lasted rather longer. It was still being used right up to the end of the series in 1959, long after Penguin had abandoned its three horizontal bands in favour of various experiments with vertical bands, other grids and even cover illustrations. But it has never quite achieved the iconic status of Penguin’s design, now used for everything from t-shirts and bags to deckchairs, and I have been unable to find out who the designer was.

It’s not clear that there was any intention at the start to use the white circle on the cover as a unifying element across different types of fiction, or to develop it as the name of the overall series. It’s not even clear that there were any plans at the start to publish fiction from other genres in similar paperback editions. It is very clear in the early books that the brand is ‘The Crime Club’ and there is no mention of ‘White Circle’ at all. It’s only from about July 1937 onwards, once other types of book have been published, that ‘White Circle’ starts to appear as a series name.

The next key decision of course was which books to publish, and here Collins were spoilt for choice. Penguin, in its early days, had to search across the market and negotiate with various hardback publishers, who were often reluctant to allow cheap paperback editions. As a result, they ended up with a lot of older books, where hardback sales had declined to a trickle. But Collins had a treasure trove of around 200 recent titles that had already been published in the Collins Crime Club and could take their pick.

Unsurprisingly they chose a more recent Agatha Christie novel ‘Murder on the Orient Express’, for volume number 1. The first 6 titles, published in March 1936, also included an Edgar Wallace and novels by John Rhode and Freeman Wills Crofts. The other two were by Philip Macdonald, one of them under the pseudonym of Martin Porlock. The next batch in June included further titles by Christie, Rhode and Macdonald as well as one from G.D.H. & M. Cole and these writers between them accounted for most of the first 30 titles, although other authors were gradually introduced.

By the time war broke out in September 1939, the series of Crime Club paperbacks had reached around 80 titles, and the wider White Circle series had extended to cover westerns, mysteries, romantic fiction, general fiction and even a small number of non-fiction titles. It was certainly in some respects a serious rival to Penguin, at least in the area of crime fiction. Even in that area, Penguin would eventually triumph, but not before the Crime Club paperbacks had reached almost 300 titles, published over a period of more than 20 years.

Was it a success in terms of broadening the reach of classic crime fiction and extending its popularity? I imagine it must have been. The print runs were probably at least 20,000 and quite possibly 50,000 or more, so sales are likely to have been far higher in paperback than they ever were in the original hardback editions. The wartime Services Editions will have extended that reach even further. But in the end, the Crime Club paperbacks did fail, presumably as another victim of Penguin when they ended in 1959, and it was the hardback editions that outlasted them, continuing right through to 1994.

Posted on February 21, 2016, in Vintage Paperbacks and tagged Agatha Christie, Albatross, Albatross Crime Club, Collins, Collins 7d, Collins Crime Club, Collins White Circle, Penguin, The Bodley Head. Bookmark the permalink. 15 Comments.

Pingback: Gunfight at the White Circle | paperbackrevolution

Pingback: Collins White Circle in Australia | paperbackrevolution

Pingback: How Crime became green | paperbackrevolution

Pingback: White Circle Westerns in Services Editions | paperbackrevolution

Pingback: John Rhode / Miles Burton in Services Editions | paperbackrevolution

Pingback: The mystery of Collins mysteries | paperbackrevolution

Pingback: Canadian White Circle books | paperbackrevolution

Pingback: Mystery stories in Collins White Circle | paperbackrevolution

Pingback: How to confuse collectors in five easy lessons … by Collins White Circle | paperbackrevolution

Pingback: Romantic fiction in Collins White Circle | paperbackrevolution

Pingback: Collins sixpenny paperbacks from the pre-Penguin era | paperbackrevolution

Pingback: 'Freshly cut grass – or bile-infused Exorcist vomit?': how crime books embraced lurid green - Non Perele

Pingback: How Crime Books Embraced Lurid Green | Gizmodo Australia

Pingback: ‘Freshly cut grass – or bile-infused Exorcist vomit?’: how crime books embraced lurid green | The Mandarin

Pingback: Hutchinson’s Crime Book Society | paperbackrevolution