Monthly Archives: December 2015

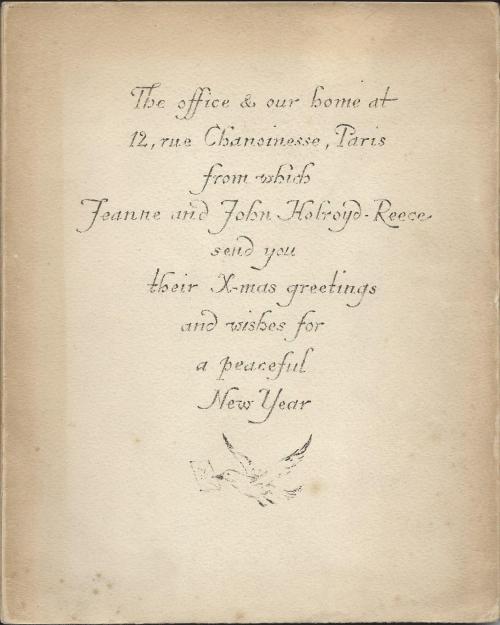

An unusual Christmas Card

The Christmas of 1938 must have been a rather tense one. The Munich agreement had been signed three months before, but Europe was sliding inexorably towards crisis and within a year it would be engulfed by war.

John Holroyd-Reece, at that point effectively the Managing Director of Albatross Books in Paris, may have had more to fear than most. The business of Albatross, selling English language books throughout Continental Europe, depended on peace in Europe, and his personal situation was both very European and very exposed to the risk of a war between Britain and Germany. He had been born and brought up in Munich as Johann Hermann Riess, to a German Jewish father and English mother, had opted for British nationality and anglicised his name, was now living in France and his (second) wife Jeanne was Belgian.

But despite the difficult political situation, he had a lot to celebrate. He was living in a magnificent apartment on the Ile de la Cité, one of the most prestigious areas of Paris, in the shadow of Notre Dame, in a building shared with the offices of the firm. Business was going well, publishing not only Albatross Books, but also the long-established series of Tauchnitz Editions, which they had effectively taken control of 4 years before.

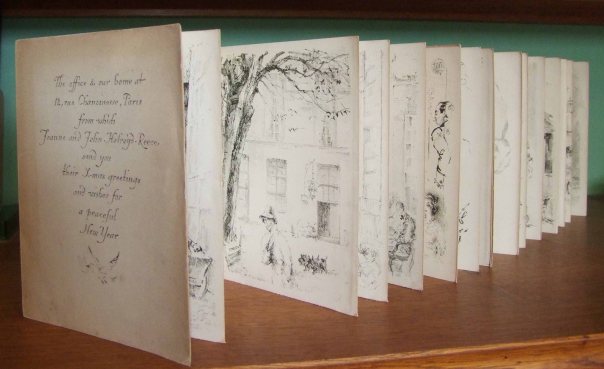

So when he decided to send out a Christmas card, it was never likely to be a simple nativity scene or a cute picture of snow, robins and holly. He commissioned an artist to produce it and ended up with an astonishing card, almost 4 metres long and folded concertina style into a 30 page booklet featuring images from their home and office.

The artist was Gunter Böhmer, then 27 years old, but who was to go on to become a significant artist across a range of styles. He was born in Dresden in Germany, had studied in Italy, and had worked at Officina Bodoni in Verona with Giovanni Mardersteig, who had created the book design for the Albatross series. In 1934 he had provided illustrations for one Albatross book – the German language edition of Dickens’ ‘The life of our Lord’, and in the course of 1938, he had illustrated another – ‘Victoria Regina’ by Laurence Housman, a series of dramatised episodes in the life of Queen Victoria. He also worked on cover illustrations for an Albatross /Tauchnitz marketing brochure at the end of 1938.

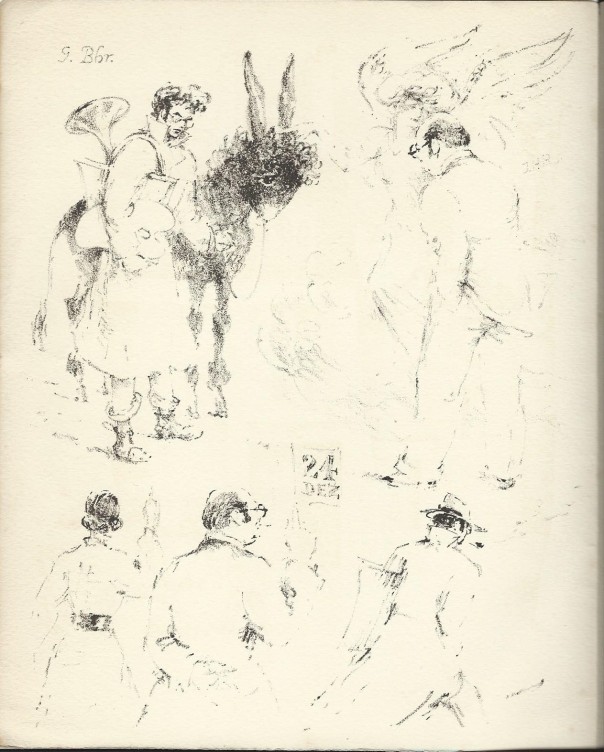

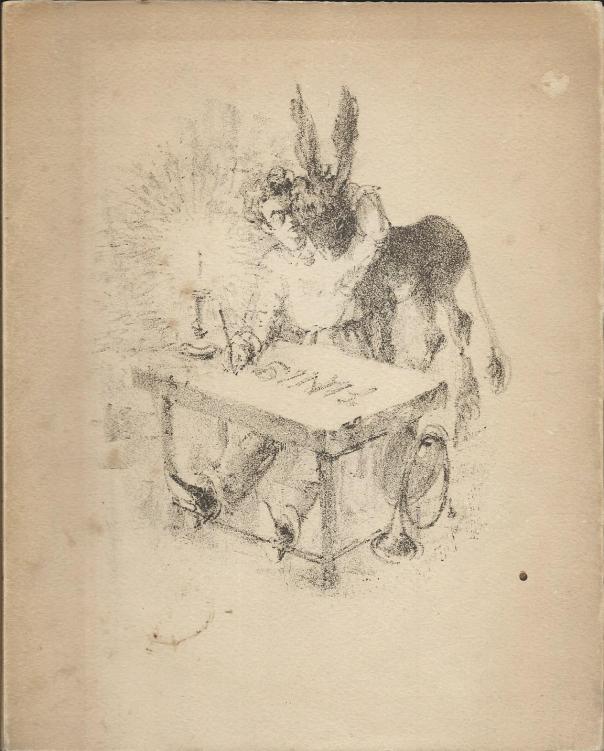

For the Christmas card, Böhmer seems to have been given free rein to produce something that not only glorified Holroyd-Reece as his patron, but extraordinarily featured a significant role for himself as the artist. He appears on the very first page of the card, apparently arriving at Rue Chanoinesse with his sketchbook, palette and a hunting horn, accompanied by a donkey, to meet Holroyd-Reece and an angel. The symbolism of the card is not always easy to understand!

Throughout the rest of the card there are images of Holroyd-Reece and his wife in various settings, both in the office and in their private rooms, and also of various other Albatross staff working in the offices. Some of the staff can be identified by initials written alongside them – ‘WO’ for Wolfgang Ohlendorf, or ‘SB’ for Sonia Bessarab for example, but others are more mysterious.

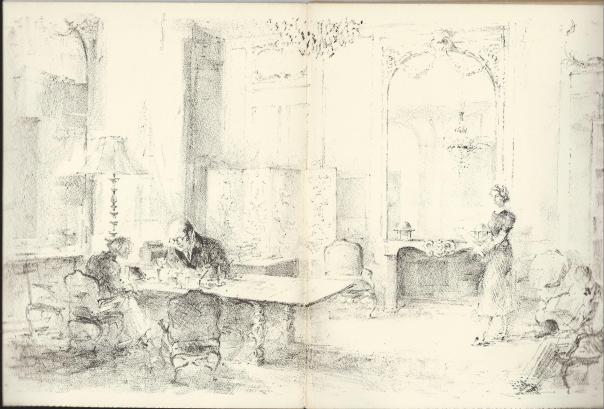

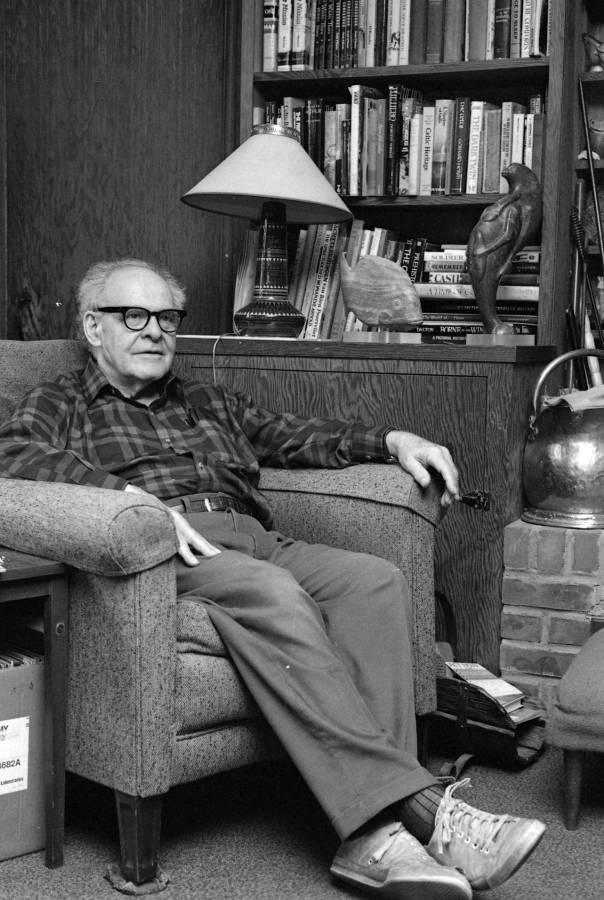

John Holroyd-Reece at work in his office

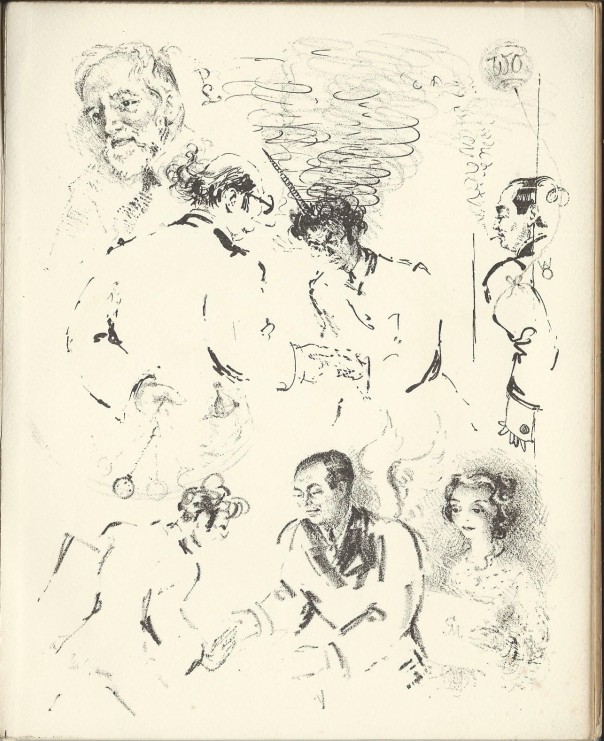

Böhmer with various Albatross staff. But why the unicorn horn?

Perhaps most mysterious of all though is the near constant presence of the artist himself, who wanders in and out of the pages of the card, before again taking centre stage at the end. He’s shown saying goodbye to the Holroyd-Reece family outside the house, before departing past Notre Dame with his donkey, in a scene that seems to evoke Mary and Joseph. The final page shows him and his donkey relaxing together with the hunting horn after a hard day’s work. I can’t think of any other work of art produced for a wealthy patron, where the artist seems to have as large a role as the patron.

The final page

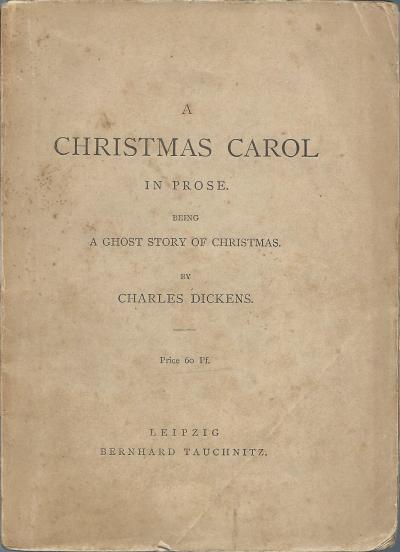

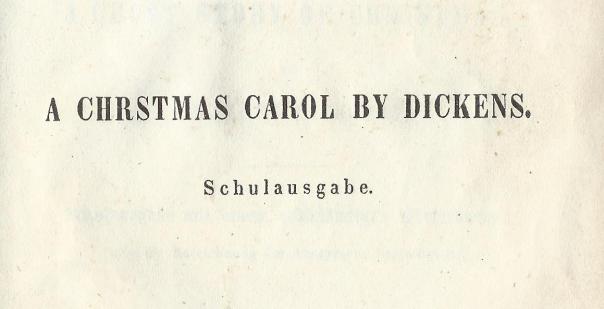

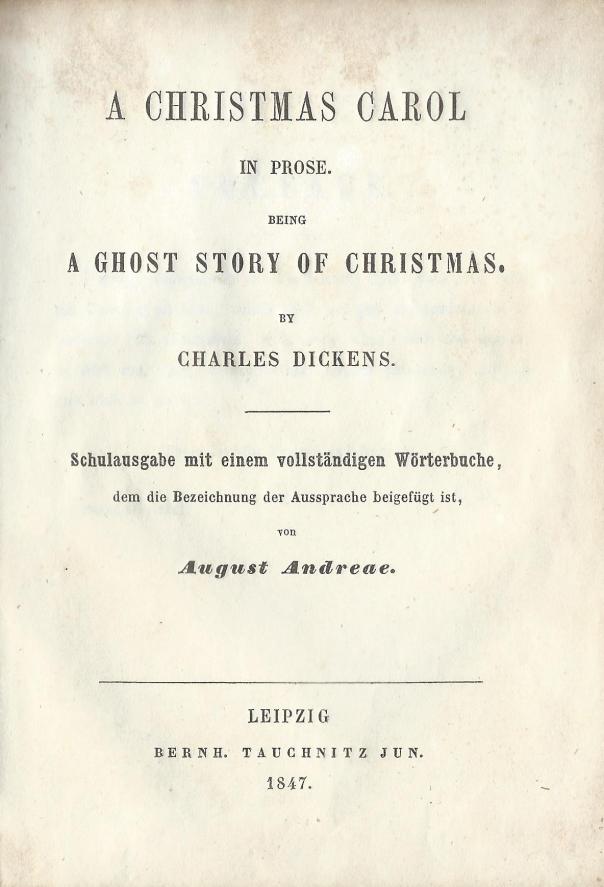

A Christmas Carol – the Tauchnitz Schools Edition

‘A Christmas Carol’ by Charles Dickens was one of the first fruits of the agreements that Tauchnitz put in place with British authors to pay them for authorised editions. In the days before international copyright agreement, most publishers paid nothing to foreign authors, but Tauchnitz decided authorisation was worth paying for.

With ‘A Christmas Carol’ he hit the jackpot almost immediately. Because of his agreement with Dickens, he received an early copy of the text and was able to get his edition out just about in time for Christmas 1843. It was almost certainly a best seller, although as a slim paperback, copies have not survived well and early or first printing copies are now rare. Later reprints are easier to find and it went on selling well for many years. Tauchnitz was still selling reprints of it not far short of 100 years later, both as an individual story and as a combined volume. Volume 91 of the main Tauchnitz series put together ‘A Christmas Carol’ with the later Christmas stories ‘The Chimes’ and ‘The cricket on the hearth’ and again this was reprinted repeatedly for over 90 years, through to the 1930s.

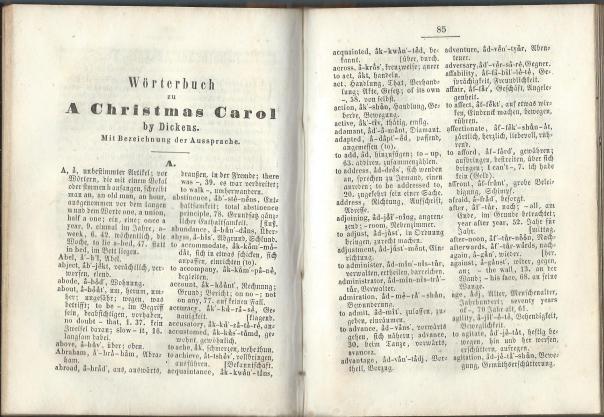

But this was still not the end of Tauchnitz’s ability to profit from the text. He also in 1847 published a Schools Edition, for which he commissioned a special English-German dictionary of the words used in the text, and a pronunciation guide. The Tauchnitz bibliographers, Todd & Bowden, recorded this edition in their ‘Additional volumes’ section and catalogued it as A7, but were able to find only a single copy of it (and that not a first printing) in any of the known Tauchnitz collections.

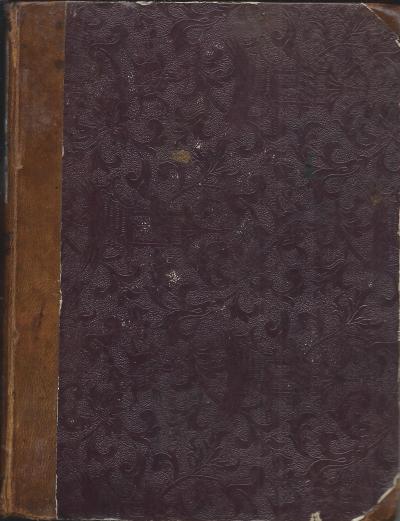

So the copy illustrated above and below is the only known example of what I assume to be the first printing of the Schools Edition. It’s distinguished by the publisher’s name on the title page being shown as ‘Bernh. Tauchnitz Jun.’ rather than the later form of ‘Bernhard Tauchnitz’. It also though has a misprint on the half-title and another in the page numbering. The text of the story itself is on pages numbered 1 to 78, exactly as the early printings of the Tauchnitz original, and was probably printed from the same plates. It’s then followed by two unnumbered pages, covering the pronunciation guide and the first page of the dictionary, before the numbering starts again from page 85, rather than 81. The copy seen by Todd & Bowden was correctly numbered from 81 through to 170, whereas this copy goes from 85 to 174.

It was presumably issued originally as a paperback, as almost all Tauchnitz Editions were, but slim paperbacks rarely survive well for 170 years, and those used in schools are probably even less likely to do so. This copy has been bound with a leather spine over decorated paper boards, and has no internal school or library markings or previous owner’s names, so may never have been used in a school.

Was this edition on general sale rather than only available to schools? Presumably there would have been some market amongst native German speakers for an edition that had a convenient dictionary at the back. Many years later, Tauchnitz launched a series of Students Editions that followed a similar format of text followed by dictionary and these appear to have been offered for general sale as well as available to schools. ‘A Christmas Carol’ featured again in this series, so the 1847 edition may just have been the first toe in the water.

The first American Penguin?

I’ve looked before at the story of how Penguin’s first operation in the US ended in tears, despite some commercial success. The management team, initially headed by Ian Ballantine, quickly ‘went native’, adapting the product so that it was much closer to other US paperbacks than to Penguin’s brand and self-image in the UK.

But all that was in the unknown future when Penguin first arrived in New York in 1939, just before the outbreak of war. Ballantine had been a postgraduate student at the London School of Economics when Allen Lane chose him to lead Penguin’s venture into the US market, and he established their first US office at 3 East 17th Street, New York in July 1939.

Ian Ballantine, much later in life

The initial plan was simply to sell books imported from Britain and for the first year or so, that was what they did. But the war made shipping books across the Atlantic increasingly dangerous. Even worse, paper was rationed in Britain and not in the US and it made little sense to send a scarce commodity in the wrong direction.

So the decision to start printing in the US was almost inevitable. But that’s all it was. A decision to print in the US some of the same books that had been published in the UK, in the same format. The British operation retained control, not only over what was printed and sold, but crucially, how it looked as well.

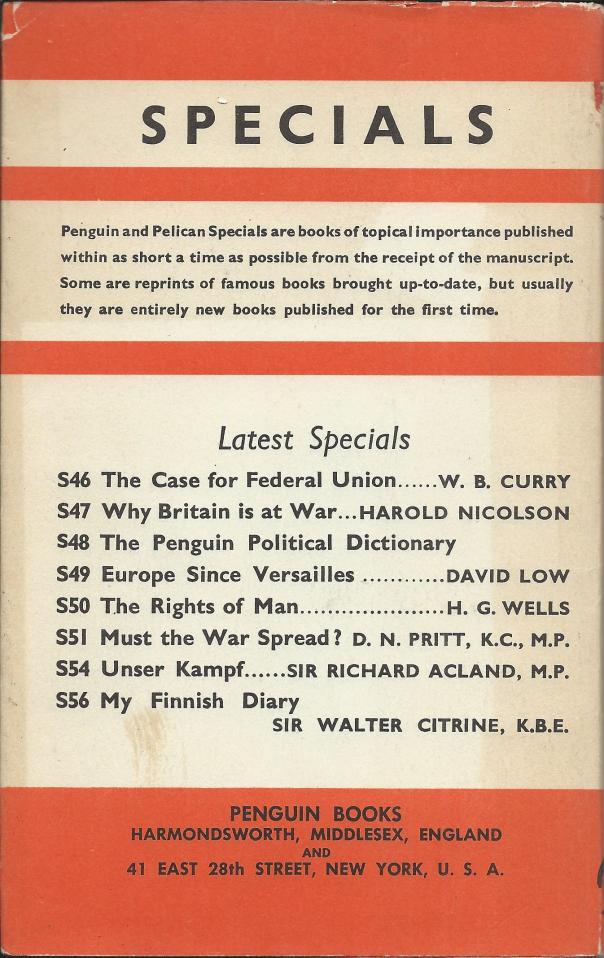

A lot of Penguin’s effort, and a lot of their success in the late 1930s and the early years of the war, had been in publishing ‘Penguin Specials’ – topical books on politics, sometimes written and published in record-breaking time to respond to the latest events, and almost closer to journalism than to traditional authorship and publishing. They sold in huge quantities in Britain, at a time when the public was eager for news and analysis of the latest political and military developments. It seems unlikely that they would have had the same impact in the US in 1940, but there was clearly some market for them.

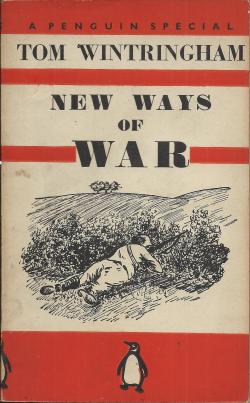

Almost certainly the first Penguin book to be printed in the US was a Penguin Special – ‘New ways of war’ by Tom Wintringham. The book, which according to the dustwrapper contained ‘full instructions for making handgrenades in any village garage’, had been written in July 1940 and published in August in the UK. The US printing is dated 1940 and so cannot have been long after. Photos of both the UK and US first printings are shown below.

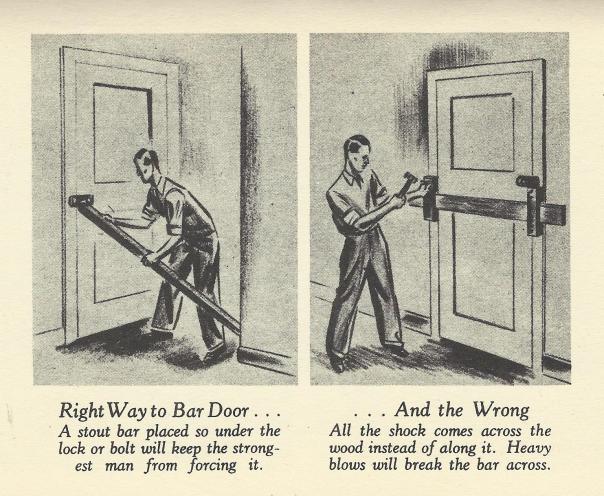

Although there are clearly some differences, at first sight it’s not obvious which is which, and both are numbered S75. If anything, the US edition (on the right) looks rather more like a pre-war UK Penguin than the UK edition does. For some reason though, the cover picture has been changed, to one that looks even more home-made than the original, and seems to show two British soldiers in extremely dangerous positions as they attempt to blow up a German tank. Other internal illustrations have also been altered and new ones added.

A new illustration in the US edition, with some idiosyncratic captioning

By this time, dustwrappers had been abandoned in the UK in the cause of wartime economy, the paper in the UK edition is of poor quality and even the colour doesn’t look quite right. The US edition is a significantly higher quality product. It has a price of 25c on the dustwrapper flap and a note on the back of the title page that it is manufactured in the US ‘by union labor’. The back cover lists other Penguin Specials with numbers S46 to S56, although it’s not clear that all of these were available for sale in the US and the list may simply have been lifted from the cover of another UK Penguin.

By this time, Penguin had moved to East 28th Street

The book also exists in a Second Printing that is undated but possibly from 1941 and also then in a Second Edition, first printed in July 1942. By that time the format has changed and it is co-published with the Infantry Journal.

Rather surprisingly, it seems to have been followed by few other locally printed US Penguins over the next year or so. I know of no other example dated 1940, and only a few from 1941. I’ll look at them another time. But it was 1942 before local printing in the US really took off in a big way.