Monthly Archives: August 2014

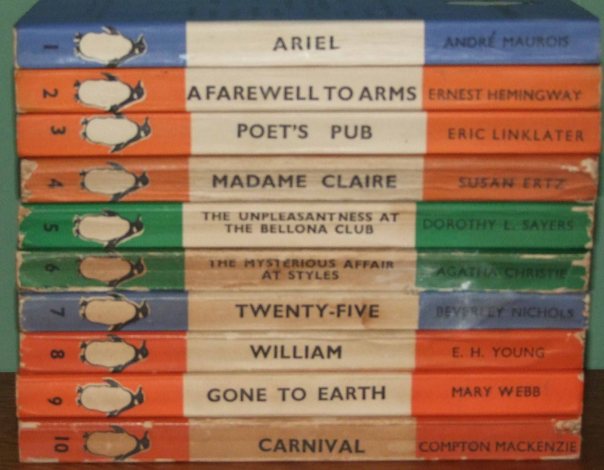

Why did Penguins have numbers?

If you p-pick up a Penguin book published recently, you won’t find a series number prominently displayed on the spine or on the half-title. When Allen Lane, the founder of Penguin, picked up the original books that he was about to republish as paperbacks, he wouldn’t have found series numbers on them. As a publisher, and Director of The Bodley Head, he had already published many books and I doubt there was a number on any of them.

Yet of all the many decisions he had to take as he set about launching Penguins, the question of whether or not to use series numbers was probably one of the easiest. They were paperbacks – of course they would be numbered. However much of an innovator or revolutionary Lane was, not to number his new paperbacks would have been a step too far.

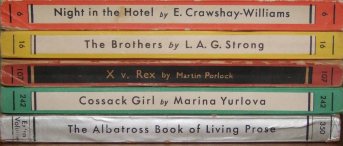

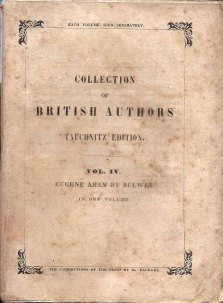

The continental Albatross Books from which Lane took many of the ideas for Penguin, had series numbers. The Tauchnitz Editions that were effectively the predecessor of Albatross, had been numbering their books since the first volume in 1842, and had reached over 5000 by 1935. In Britain too, paperbacks were almost always numbered. The Hutchinson paperback series of ‘Famous sixpenny novels’ had already gone past 400 and Victorian paperbacks such as W.T. Stead’s ‘Books for the Bairns’ and ‘Penny Poets’ had all been numbered. There were certainly a few hardback series that were numbered as well, but the general rule was to issue paperbacks as a numbered series and hardbacks as individual books.

Albatross paperbacks and an early Tauchnitz paperback

But why? Was it that paperbacks were seen as more like magazines than books? Magazines had traditionally been numbered, although often split into in volumes, rather than just numbered sequentially. Newspapers, even today, are often numbered – The Times is currently over 70,000, The Independent at a more modest 8,500ish.

Did it go back to the days when novels, such as several of those by Dickens, were sold as a series of parts, in numbered paperbacks? Or was it just that paperbacks needed the branding of a series, whereas hardbacks sold more on the reputation of the author, or the cover illustration. The logic doesn’t seem to apply any more, as few paperbacks are now numbered, or have any conspicuous series branding or publisher branding.

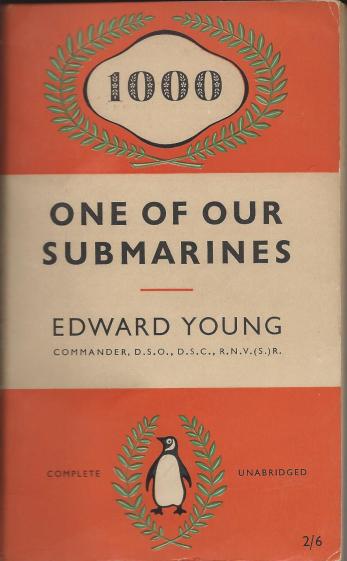

Whatever the reason, Penguin came to love their numbers. Special numbers soon became reasons for celebration. George Bernard Shaw was the prime celebratory author in the early days, being given numbers 200, 300 and 500. Volume 1000 was saved for a book by Edward Young, a former Penguin employee who had drawn the original logo, before going on to become a submarine commander. It was followed by volume 1001 – ‘The thousand and one nights’. Earlier, number 666 had been used for ‘Defy the foul fiend’.

From the point of view of modern day collectors, series numbers are a great help, making it much easier to see what exists and which books are missing. They almost provide a rationale for collecting – to find the first 100 or the first 1000 Penguins – although they also provide some intriguing mysteries, where numbers are missing or duplicated or inconsistent.

Penguin eventually stopped showing series numbers on their paperbacks some time around the 1970s, although they couldn’t entirely kick the habit. Almost alone amongst major publishers, they continued to print the ISBN at the bottom of the spine, from which a series number could be inferred, for almost another twenty years before eventually deciding it was entirely redundant.

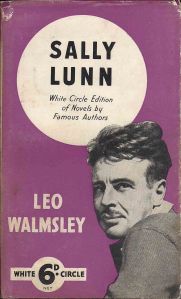

Back to basics – Collins White Circle paperbacks

This blog was supposed to be mostly about books, particularly vintage paperbacks. It’s been rather taken over by theatre reviews and travel writing, but it’s time to get back to basics.

And what could be more basic than Collins White Circle paperbacks? Although they followed in the footsteps of Penguin Books, launching less than a year later, in 1936, they had little of Penguin’s high-minded idealism. At heart they were a publisher of genre fiction – crime, mystery, westerns and romance. But they still followed the basic Penguin formula – standard size, standard price of sixpence, standard covers with colour and design indicating genre, but otherwise un-illustrated, dustwrappers in the same design as the cover.

Standard cover designs for the Wild West and Crime Club sub-series

On the face of it this is a bit odd. There were plenty of paperbacks for sale before Penguin, and many of them were precisely in this market sector of genre fiction. The one thing that they had in common was illustrated covers, often very gaudily illustrated. Penguin’s innovation was to bring in soberly designed covers, aimed at a different audience, cultivating an image of seriousness, if not intellectual snobbery. Even if Penguin’s actual output didn’t always match this image, there was at least a consistency in their branding. But why would a publisher of genre fiction use such similar branding?

Mystery and romance cover designs

The answer presumably is that in reality the market sectors the two publishers were aiming at were not so different. This was the golden age of detective fiction and the Collins Crime Club hardbacks had achieved a level of intellectual credibility and middle class acceptance. Many of them had already been published as up-market paperbacks on the continent in the Albatross series that was Penguin’s inspiration. Illustrated covers would have signalled a move down market. Collins were probably aiming rather more up market than usual for genre fiction, and Penguin were aiming a bit more down market than they’d have liked to admit. After all, Penguin’s own output included a significant number of crime titles.

The few general fiction titles had more individual cover designs.

The White Circle series seems anyway to have been successful, and by the outbreak of war in 1939 it ran to almost 200 books. Penguin by that point had reached about 220 in their main series, although they had also diversified in various other directions, notably into non-fiction through Pelicans and Penguin Specials. With production in the UK hampered by war-time restrictions, Collins too had to diversify, launching a long series of White Circle Services Editions and exporting the White Circle brand to Canada, India and Australia. All that’s a story for another day though, as is the renaissance of the series after the end of the war, when it continued to challenge Penguin for another 15 years through to the end of the 1950s.

‘Great Britain’ at the National Theatre

Wow! It’s not difficult to see why the lawyers did not want this play performed, or even announced, while the phone hacking trial was going on. It’s a satire, but like all the best satires, it’s sufficiently well grounded in reality to hit home and to avoid descending into farce. Of course the characters are caricatures, but at times it’s scary how ludicrous it can get without becoming detached from reality. Hacking into the voicemails of abducted children, tabloid editors in bed with the police and politicians, press campaigns leading to the hounding of innocent people, police shooting an unarmed black man, journalists searching through the bins of celebrities and paying civil servants for confidential information, politicians desperate for media endorsement and conspiring to keep their own indiscretions hidden, police deliberately ignoring evidence of widespread criminality, media owners cynically controlling politicians to further their own financial interests… all of this ought to be farcical, but at times seems little more than documentary.

Richard Bean’s play has masses of energy and the cast bring some real verve to it. Billie Piper romps through the play, as tabloid editor Paige Britain, delivering monologues of breath-taking cynicism to the audience, as she manipulates everyone from her closest colleagues to the police and the Prime Minister. It’s clear from the start that it’s going to be an uncomfortable ride, as she forestalls any hint of smugness from Guardian-reading liberals, and she’s back at the end to make us all feel at least partly complicit in what went on.

She has some great lines, but certainly no monopoly on them, and there are plenty of laugh-out-loud moments. Aaron Neil does a great comic turn as the witless Police Commissioner, which he plays absolutely straight-faced. A personal favourite was his mangling of the already mangled Donald Rumsfeld quote on known unknowns, and the way some of his lines were given the Nick Clegg treatment in Youtube-style videos on giant screens seemed almost ground-breaking. I’ve seen several plays before that have used screens and audio-visual elements, but nothing before that harnessed new technology and integrated it into the live action so effectively. It’s also quite impressive that a serious role is given to an actress with dwarfism, although they can’t resist using it for some deliciously politically incorrect jokes.

Maybe some of the targets were a bit too easy, maybe even there were too many disparate targets for any serious analysis of the reforms needed, but overall it felt to me like a triumph, and certainly a gloriously enjoyable afternoon in the theatre.