Monthly Archives: July 2014

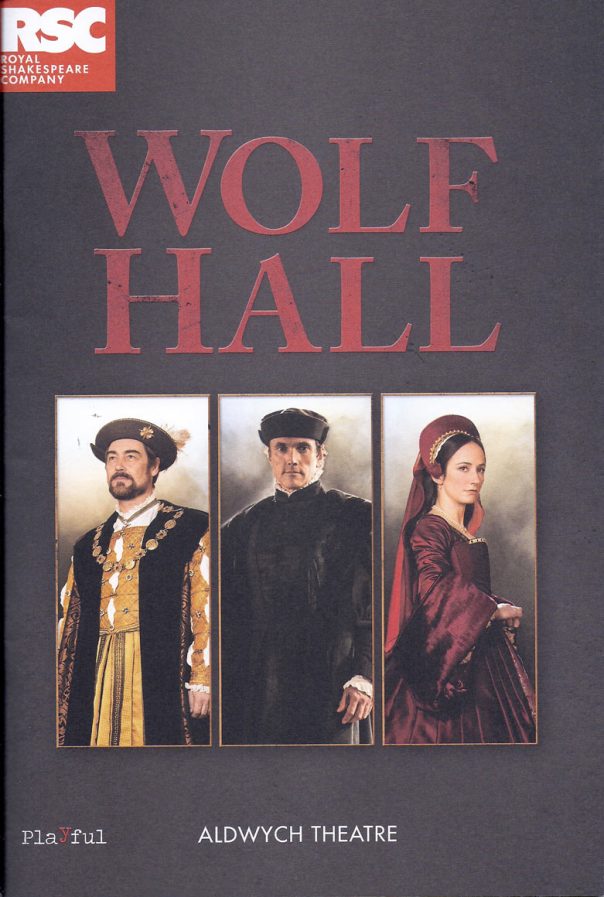

Wolf Hall and Bring up the bodies – RSC at the Aldwych

If there’s such a thing as the RSC house style, then I’m a fan of it. The plays they put on always seem to me to be well acted, well spoken and above all, well directed. It’s almost always an enjoyable and rewarding experience watching one of their productions, regardless of the quality of the play and regardless of whether there are star actors in the leading roles. But for the most part the material they have to work with, being written by Shakespeare, is of course of the highest quality.

When they move away from Shakespeare, as with ‘The roaring girl’ that we saw last month, and now with ‘Wolf Hall’ and ‘Bring up the bodies’, they can’t be so confident of the quality of the material,, and with no real star names in the cast, they need the fundamentals of good direction and good acting to carry them through. And it does, as ever. Both of these plays were thoroughly enjoyable and a rich theatrical experience.

The novels on which they’re based have been a huge commercial and critical success, each winning the Booker prize in a unique double success. The plays have been similarly successful, and the packed audience was clearly enthusiastic. But I still have doubts. While I suppose most of the audience were already fans of the books, I’ve made only limited progress into the first one, so the plays had to be judged largely on their own. Did they have enough dramatic structure to stand up as individual plays if you saw them separately and hadn’t read the books? Did they have anything much to say beyond a narrative of what is certainly a fascinating period of English history? What are their themes and do they have anything to say about them? In a number of areas they seem disappointingly ambivalent.

Are they about the exercise of power? There are plenty of hints that both Thomas Cromwell and Cardinal Wolsey are guilty of some pretty horrific crimes in their personal quests for power and wealth. Both could easily be characterised as evil. But this is no Richard III – their portrayal is essentially sympathetic, Cromwell, on stage for almost the entire 5 hours, is treated almost as a hero, and Wolsey almost as a saint, offering advice from beyond the grave. Thomas More on the other hand, the one character who might be thought to act on principle rather than pure self-interest, and who actually was made a saint after his death, gets a most unsympathetic portrayal. Where is the morality in this production, or is it simply saying that power and self-interest will triumph over morality?

Another theme might be religious freedom, but here again it is strangely ambivalent. There are early hints that Cromwell and Anne Boleyn are motivated by some real attachment to Luther and the new movement of Protestantism. But this is barely credible in the light of the rest of the play where they are much more nakedly motivated by self-interest. You feel they would happily have paid homage to a strong Pope in control of armies that could have helped them, just as they were happy to cut the ties to a weak one, in favour of a King who can advance their careers and their interests.

So is it about loyalty? A large part of the second play is taken up with Cromwell’s settling of scores with all those who contributed to the downfall of Wolsey. The conclusion even hints that as a final settlement he might consider regicide. Again all this is given a very sympathetic portrayal. Are torture, murder, false accusations, all fair game if they are done out of loyalty? It’s unclear where Mantel, or Mike Poulton, who adapted the books for the stage, stand on any of this.

Or what about class? Much is made of the fact that Cromwell comes from a poor background in Putney, and that Wolsey’s father was a butcher. This is a mocking refrain throughout the plays from those who have gained their position and wealth as an accident of birth, although there is no hint that this troubles our heroes in the slightest, or impedes their success. Our natural sympathy is with those who have risen through their own efforts, although again, with little questioning of what methods they are using to achieve that.

Even on the central question of the second play, to what extent Anne Boleyn engaged in adultery, the plays seem studiedly neutral, with the possible answers ranging from on a regular basis, including with her brother, to not at all. That may be the historian’s view as well, but this is a play not a history.

One clear conclusion from seeing these plays performed in London is how wonderful the Stratford stages are. I’m more used to seeing the RSC perform there and you’re much more involved in the whole experience. Here we were near the back of the stalls, underneath an overhanging dress circle, a long way from the stage and with an effectively restricted view. I’m told that the stage was dominated by a large cross, but there’s no way I can confirm that from where I was sitting.