Monthly Archives: December 2014

The Penguin Forces Book Club

Penguin did not often get it wrong in the early days. From the very start it seemed that almost everything they touched turned to gold. Sales of their early books soared, but instead of just carrying on in the same direction they launched into a flurry of activity in all directions. The main Penguin series launched in July 1935 and by the end of 1937 had reached well over 100 books. But by then it had also been joined by a non-fiction series, Pelican Books, by a series of Penguin Shakespeare and by the first in a series of topical books on politics – the Penguin Specials. All these were to go on to be long-running and very successful series. Even in wartime, Penguin continued to innovate and expand in new directions. The King Penguin series started at the end of 1939 and was to run for over 15 years. Puffin Picture books followed in 1940, and Puffin Story Books in 1941. Both series are still running today, in spirit if not in name. Allen Lane it seems was a restless spirit, unable to rest on his laurels.

There was the odd exception and wrong turning of course. The Penguin Illustrated Classics was limited to one set of 10 books in 1938, and launching a series of travel guides just before the outbreak of war was perhaps not the smartest idea. But these were relatively small mistakes and quickly dealt with. So the Penguin Forces Book Club stands out as an area where Penguin got it badly wrong and had to spend a lot of time and effort correcting their errors.

The basic idea was a good one. There were lots of people in the Services with time on their hands for reading. Even the front line troops were not always continuously occupied by the business of war, and behind the lines there were plenty of air raid wardens and the like who had long hours of inactivity to pass, as well as all the wounded servicemen in hospitals. The public had already been asked to send in books they had read and the Services Central Book Depot would send them off in parcels to service units. Printing paperback books specially for the forces was not only a good idea, but one that was eventually to result in the massively successful programme of Services Editions in the UK and the equivalent Armed Services Editions for the US forces.

It was a good idea and Penguin was there first. Unfortunately they got the details wrong in almost every respect. Their marketing was wrong, their distribution model was wrong, their financial model was wrong, their choice of titles was wrong and their numbers were way out. The agreed model was that Penguin would provide 10 books each month, so 120 books in a year at a cost of 6d each, a total cost of £3 to be paid as an advance subscription. But service units didn’t want to pay in advance for books that they would receive over the year and they were not impressed with Penguin’s choice of titles. The first monthly set of 10 books included 2 crime stories, but also 2 scholarly Pelicans (‘Cine-biology’ and ‘Ur of the Chaldees’), 2 current affairs books from the Penguin Specials series and a memoir on life in China. Future monthly selections followed a similar pattern. Publicity for the scheme seems to have been limited, and from an initial planning estimate of obtaining 75,000 subscriptions, the numbers reduced to around 6,350 in January 1943, four months into the project.

The books of course are rare today, some of them extremely rare, but overall they’re perhaps not as rare as might be expected from such low numbers, and they crop up in a variety of formats. Penguin may well have printed significantly more than 6,000 and then had the problem of how to get rid of them. I’ll come back to this some time in another post.

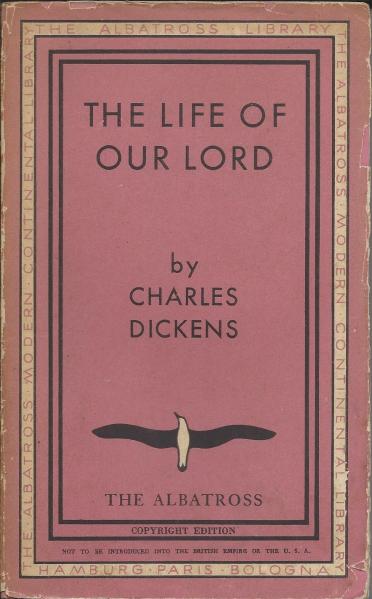

An unusual Albatross from Charles Dickens

Charles Dickens more than any other author had helped to make the reputation of the Tauchnitz Editions in the 19th century. All of Dickens’ novels appeared in the Tauchnitz series and in some cases the Tauchnitz Editions are the true first printings in book form, printed from early proofs of the part-issues. There were also numerous volumes reprinted from the Dickens magazines, ‘Household Words’ and ‘All the Year Round’. The personal relationship between Charles Dickens and Bernhard Tauchnitz was very strong, as illustrated by the correspondence featured here a few weeks ago.

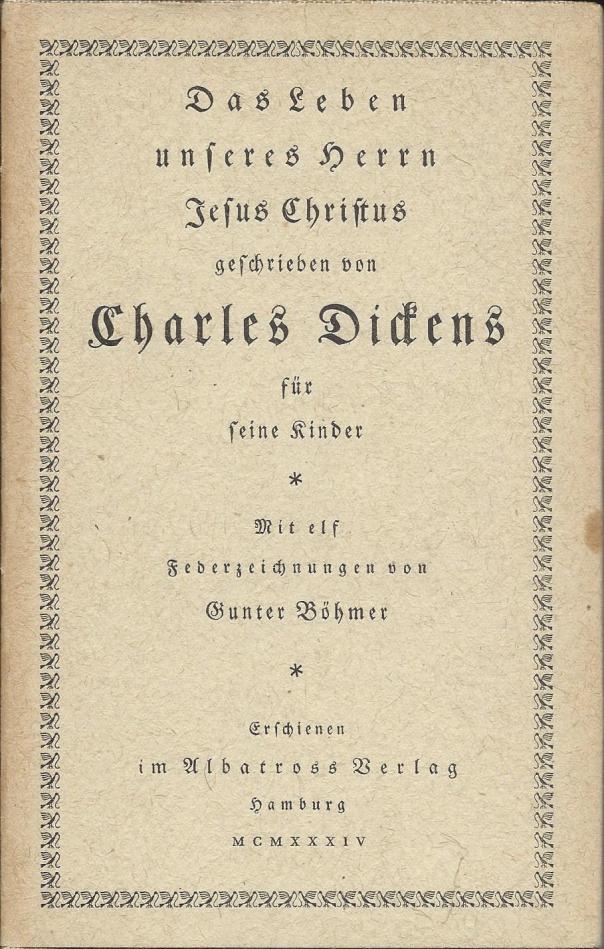

But all that was in the 19th century and was ancient history by the time Albatross appeared on the scene in 1932 as the latest challenger to the long-established Tauchnitz. They recruited a large number of authors previously published by Tauchnitz, but they can hardly have imagined that Charles Dickens would be among them. So it was something of a coup for them to obtain the right to publish Dickens’ version of the life of Jesus, written for his children, when it was released by his family in 1934. Dickens had not wanted it published, but after his death a handwritten version was passed down through his family, and continued to be read at Christmas.

When publication was finally agreed, the rights were handled by Curtis Brown literary agents, who had played a role in the original creation of Albatross. In most cases the rights to continental publication could not be obtained for at least a year after first UK publication, but in this case the delay seems to have been waived and Albatross obtained the rights not only to publish an English language version in continental Europe (which appeared as Albatross volume 207), but also to publish a German language edition. By this point in 1934 Tauchnitz were close to collapse, and it is almost as if the loss of Dickens to Albatross was the final symbolic blow to their heart. Before the end of the year, Tauchnitz had been sold to the printing firm of Brandstetter and editorial control had passed to Albatross.

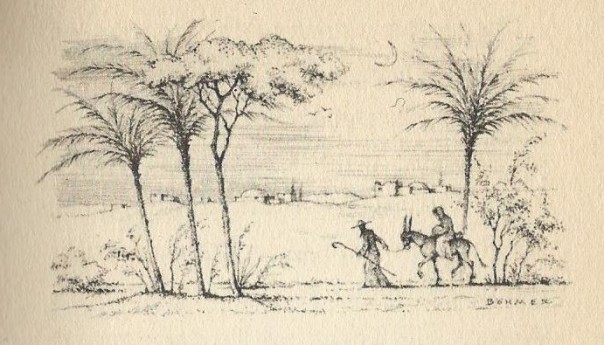

The English language edition of the book was more or less a standard Albatross book. As the text is relatively short, it appeared in a large font size, and with wide margins, but still only stretched to 140 pages. The paper seems to be thicker than for most other Albatross books, presumably to bulk it out, but also of poor quality and subject to page browning. The German language version though is another matter, and seems to have been treated as a prestige publication. Unusually for Albatross, it’s a hardback book, written in Gothic Fraktur script, with illustrations at the heading of each chapter, and with a dustwrapper on heavier paper than normal. It was translated into German by Hans Mardersteig, who had been responsible as designer for the original design of the Albatross books when they launched in 1932, and the illustrations and book design were by Gunter Boehmer, a young German artist (then only 23) who was later to become much better known, and also to have other connections with Albatross. I’ll come back to those later, but there’s a brief preview here.

The Christmas Truce – RSC at Stratford

Does Phil Porter’s play create an over-sentimentalised view of war? Certainly it’s the First World War as family entertainment, the RSC’s Christmas show aimed at families and recommended for children over the age of nine. But even nine year olds these days are raised on a diet of much grittier action than this. Video games, such as Call of Duty, may be aimed at slightly higher ages, but the third Hobbit film, which I saw this week, is certainly aimed at anybody over the age of 9 and it has plenty of decapitations, stabbings and generally graphic, if slightly cartoonish, violence.

Here instead we get a nurse singing Ave Maria and war reimagined as cricket, as well as the expected soldiers singing ‘Silent Night’, exchanging cigarettes and kicking around a football.

The question is prompted in part by an article by Sebastian Borger, a German journalist based in London, who finds himself bemused by the British attitude to commemorating war. The trigger for his article was the Sainsburys Christmas ad, again based on the Christmas truce, and effectively using it, with the British Legion’s endorsement, to sell carrots and Christmas puddings. But it could equally have been the poppies at the Tower of London, a magnificent and moving spectacle, but one carefully calibrated to record the number of purely British military dead and treading a fine line between commemoration and celebration. Or it could have been this production. It seems undeniable that there’s been a sentimentalised side to the way that the First World War has been represented in British culture in this centenary year.

Certainly this production has none of the hard-hitting punches of ‘Oh what a lovely war’ – a show that’s perfectly suitable for viewing by families, even for performing by children as I’ve seen in the past. There the description of a lovely war is loaded with irony – here at times it comes close to prosaic description, as the soldiers perform in an extended concert party routine and then kick a football around with their opponents. There are certainly darker moments and every time the action veers too close to celebration or sentimentality it has to be brought back to reality. The brightly lit opening game of cricket suddenly switches to a dimly lit recruiting office, an impromptu game of target practice between the opposing trenches is ended by a soldier being shot in the head, and the concert party is followed by the news that the soldiers are being sent over the top the next day. The casualties are grimly recorded as the fall of wickets on the cricket scoreboard.

But the overall mood of the play is light and if that’s accepted as appropriate, it’s beautifully done. The idea of basing the story around Bruce Bairnsfather, one of the most celebrated cartoonists of the First World War, and a local Stratford man, works really well, and there are good performances from both Joseph Kloska as Bairnsfather and Gerard Horan as Old Bill, his most famous character brought to life. Unfortunately the scenes set in a military hospital work much less well. Were they intended as a counterpoint to the grimness of the trenches, or more cynically just as a way to create some female parts in the production, particularly as it is played by largely the same group of actors as are currently playing two other productions with stronger female parts? Either way they feel forced and the arguments between a nurse and a matron feel artificial, set up to create an unrealistic parallel with the truce being played out by the men.

Whatever my doubts about the sentimentality and the structure of the play, I have to say that it was wonderful entertainment, and I guess that was its main aim. There are one or two deeper moments, as when Bairnsfather initially refuses to shake the hand of his German counterpart, prompting a reflection on how little difference there really is between the sides and between the ordinary soldiers, or when he tackles his commanding officer who insists on curtailing the truce, but these are exceptions. This is not a play about the futility of war, or one that draws any meaningful parallels with modern wars (anyone for a Christmas kickabout with Islamic State?). It’s just a very entertaining family show for Christmas. If that involves lots of carols and a thick layer of sentimentality, well that’s OK. There’ll be plenty of harder reality in the New Year.

Ulysses in plain covers

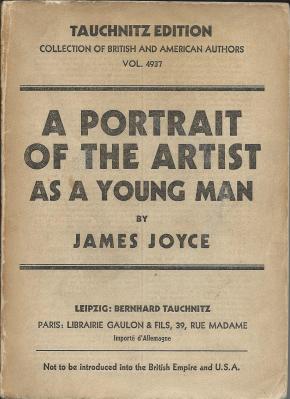

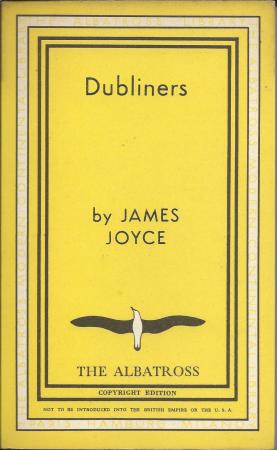

James Joyce has a special place in the story of Albatross Books. The very first Albatross, published in 1932 was ‘Dubliners’ by Joyce, and in some ways the connection goes even further back than that, to the point when Max Wegner became General Manager of Tauchnitz in 1929. By that point, Tauchnitz was living on past glories and had lost most of its earlier dynamism. Wegner set about shaking it up. Amongst other things, a search through the file found correspondence from Joyce 10 years earlier about plans for Tauchnitz to publish ‘A portrait of the artist as a young man’. It had never appeared. Wegner arranged for it to be published, and it finally appeared in May 1930 as Tauchnitz volume 4937.

Other Joyce books might well have followed, but Wegner’s changes at Tauchnitz were too much for the Board, which forced him out by mid-1931. It was a catastrophic decision. Wegner played a key role in the establishment of Albatross the following year as a rival to Tauchnitz, and by 1934 the new firm had effectively taken over the old one. It seemed fitting that ‘Dubliners’ became the first Albatross book, rather than the 5000 and somethingth Tauchnitz.

But Wegner and John Holroyd-Reece, the head of Albatross in Paris, had other plans in mind for Joyce as well. After ‘Dubliners’, it was natural to look next at ‘Ulysses’, which had been published in Paris 10 years earlier and reprinted several times, but was effectively banned in the UK. For the ‘Albatross’ edition, it was revised by Stuart Gilbert, at Joyce’s request, and carries a note saying it ‘may be regarded as the definitive standard edition’. That’s a substantial claim for a notoriously complex book that has been plagued by errors and misprints, but I think it’s fair to say that many people still regard this edition at least as an important one in the book’s publishing history, if no longer the definitive one.

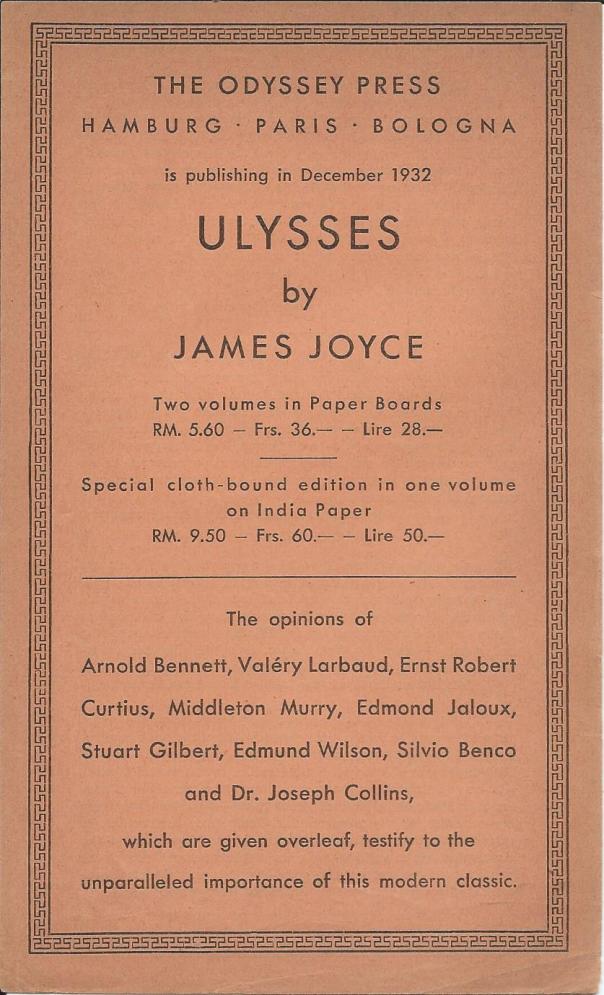

The two volume Odyssey Press edition of Ulysses

But is it really an Albatross? It doesn’t immediately look like one, published in two volumes in almost plain covers, and bearing the imprint of The Odyssey Press. It does though have the standard size of an Albatross and the layout of the books is almost identical to other Albatross Books. It has the typical blurb in three languages on the cover, the same style of title page and copyright notice at the front and the characteristic Albatross colophon at the back, showing it uses the same typeface, the same paper supplier and the same printer as other Albatross Books from that period.

In practice The Odyssey Press (as the name might suggest) was an imprint set up specially for this purpose by Albatross, presumably because they were concerned that the book might not be consistent with the brand image they were trying to create for Albatross. They used the same imprint a few months later for publication of ‘Lady Chatterley’s lover’ as well – another book that at the time was banned in Britain. In some ways this feels like an excessively cautious approach to us now, but modern publishers too are concerned about establishing and protecting their brand image, so we shouldn’t judge them too harshly.

And in reality it was an Albatross – indeed very specifically it represented volumes 43 and 44 of the Albatross Modern Continental Library. Those volume numbers never appeared on the book and Ulysses didn’t feature much alongside other volumes in Albatross marketing, so the numbers are missing from most Albatross lists of titles, but there’s no doubt that that’s what they were. Lady Chatterley’s Lover similarly appeared in plain covers, but was allocated volume number 56 in the Albatross series.